—————

—————

Hellraisers Journal – Monday March 4, 1912

“The Battle for Bread at Lawrence” by Mary E. Marcy, Part I

From the International Socialist Review of March 1912:

THE strike of the 25,000 textile workers at Lawrence, Mass, came so suddenly that the Woolen Trust was overwhelmed. It started January 12, pay day at the mills. Without warning the mill owners docked the pay envelopes of their employes for two hours in time and wages as a result of the new 54-hour law which went into effect January first.

The drop averaged only 20 cents a worker and the American Woolen Company fondly imagined that their wage slaves had been sufficiently starved and cowed into docility to endure the cut, just as they had suffered a speeding up of the machines so that the output per worker in 54 hours was greater than it had been on the 56-hour basis.

But trouble started with the opening of the docked pay envelopes, and before the day was spent, Lawrence had a wholly unexpected problem on its hands. The disturbance spread quickly and within an hour 5,000 striking men and women were marching through the streets of the mill district, urging other mill workers to join them.

Their number was augmented at every step and soon

Ten thousand singing. cheering men and women, boys and girls, in ragged, irregular lines, marching and counter-marching through snow and slush of a raw January afternoon—a procession of the nations of the world never equaled in the “greatest show on earth”—surged through the streets of Lawrence…..You listened to the quavering notes of the Marseillaise from a trudging group of French women and you heard the strain caught up by hundreds of other marchers and melting away into the whistled chorus of ragtime from a bunch of doffer boys. Strange songs and strange shouts from strange un-at-home-looking men and women, 10,000 of them; striking because their pay envelope had been cut “four loaves of bread.”

—-The Survey.

As a matter of fact the “violence” bewailed by the mill owners consisted probably in half a dozen windows smashed on the first day of the strike, for the strikers were busy holding mass meetings under the auspices of the I. W. W. on the days following, and planning ways for carrying on and extending the fight.

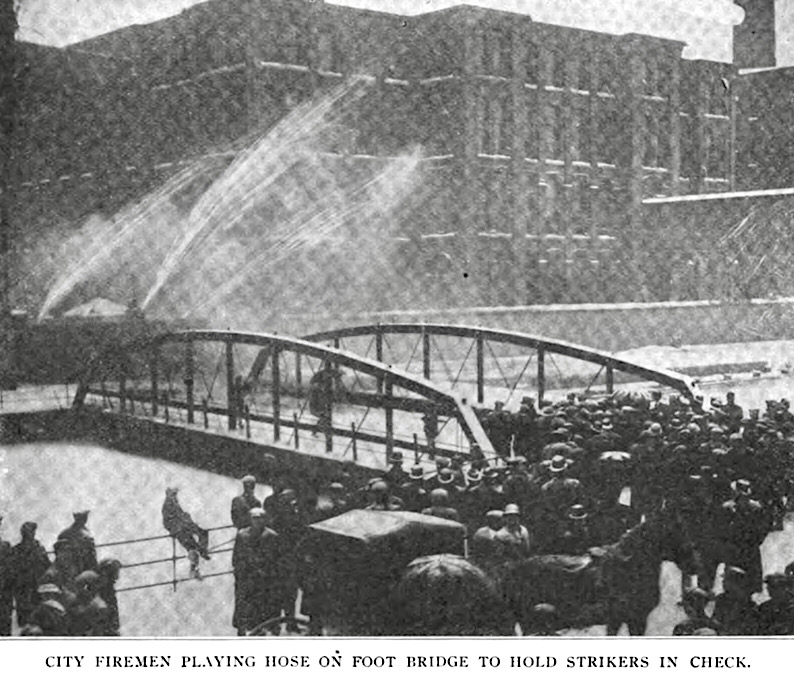

But the redoubtable Mayor of Lawrence knew his duty to the mill owners and he did not flinch. When the strikers, blue and shivering in the keen 10 degrees below zero January wind, decided that the city hall was better suited for mass meetings than the commons, Mayor Scanlon burned his protestations of concern for the workers and the business men of Lawrence, behind him, and called for the militia.

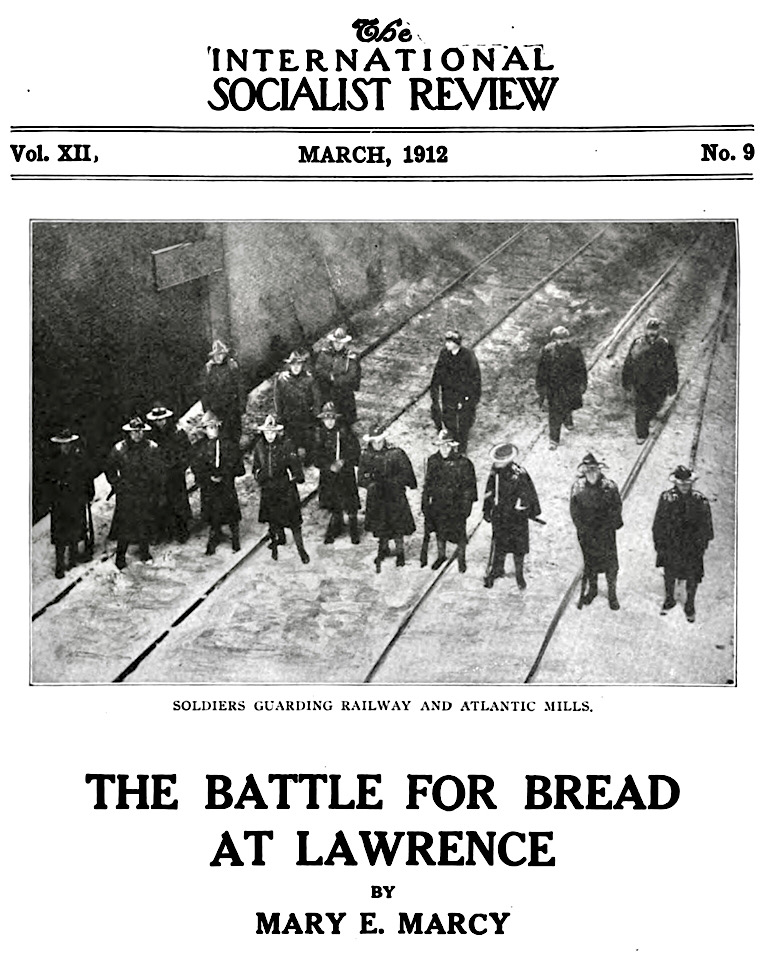

Even the capitalist press, which has ever been notoriously unfair to the working class in its struggles with the employers, reported that outside of preventing the besmirchment of the precincts of the city hall by working class boots, soldier duty for the first week of the strike consisted in looking wise and parading the mill district.

Mr. Lewis E. Palmer says in the Survey, February 3:

The Boston reporters did their best to manufacture daily stories about outbreaks between soldiers and strikers and they usually managed to draw good bold face lines from the head writers. The newspaper photographers were everywhere and perhaps the best example of their art was a picture of one of their own number being “repelled at the point of a bayonet” by a citizen soldier who was trying hard to “see red.” By January 22 Col. E. Leroy Sweetser had a complete regiment of militia at his command, and some people wondered why.

Now everybody knows that the Woolen Trust has based its demands for a higher protective tariff on wool on the alleged necessity of paying higher wages in America than are necessary to support workers abroad. The claim has been made for the past thirty years that the protective tariff was levied primarily for the protection of American workers “against the pauper labor of Europe.” But it has come about that the American workers have been reduced to pauperism under the benign influence of high tariff.

Wm. N. Wood, president of the American Woolen Company that operates these mills, is a very particular friend of both Taft and Roosevelt, as has been made manifest by the substantial favors bestowed on him by them as chief executives of the United States.

The Woolen Trust controls more than thirty-two of the largest mills in America. Its plants cover over 650,000 acres and its stone shops contain more than 11,000,000 acres of floor space. In seven years the trust has paid out over $25,000,000 in dividends and accumulated a surplus of over $11,000,000. So much for the mill owners. Turn now to the condition of the workers. Mr. Palmer says:

In a dingy back room of an Italian house I saw over fifty empty pay envelopes which had been returned to the bank as representing average wages of men employes. The amounts written on those envelopes together with the character of the work performed are classified as follows:

It would seem that, wrapped up in all the red tape of Schedule K, their excellencies, the two Williams, have delivered a full sized joker to the working classes of America.

The primary cause of the strike, a cut of 22 cents in the weekly wage was, after the arrival of Joseph J. Ettor, organizer for the Industrial Workers of the World, merged into a series of demands. These demands included a 15 per cent increase in wages, the abolition of the bonus and premium system and double pay for overtime work.

With the accession of Ettor a new spirit of militancy began to permeate the strikers. Too late the mill owners offer to grant the original demand. But the new spirit of solidarity among the men and women, bringing with it a sense of their own power, welded them together in a determination to secure more of their product—to improve their condition.

Detectives in the employ of the Woolen Trust appeared overnight, and with their advent, dynamite scare-headlines began to work their way to the front pages of the metropolitan dailies, charging the strikers with attempts to blowup the mills.

The police made arrests on the slightest provocation and the fine social sense of Judge Mahoney, who has dealt out the severest sentences possible, is shown in a statement which he made in disposing of the case of Salvatore Toresse. The judge said: “This is an epoch in our history. Never can any of us remember when such demonstrations of lawless presumption have taken place. These men, mostly foreigners, perhaps do not mean to be offenders. They do not know the laws. Therefore the only way we can teach them is to deal out the severest sentences.” Toresse was fined $100 for intimidation and $10 for disturbance and given six months for rioting. (The Survey.)

Commenting on the fact that the innocent workingmen arrested on a charge of dynamiting were still being held, the Lawrence Leader, of January 28, says:

It is no longer whispered—it is being almost published from the house-tops—that a cruel, wicked conspiracy to discredit the strikers was framed-up and the dynamite “planted” where it could be “found” quickly. The object, it is said, was not so much a newspaper fake as it was to turn public sympathy abroad from the strikers and to lead the world to believe that reckless, dangerous anarchists were the ringleaders of the strike.

Members of the state police have practically admitted that the whole business was a frame-up. It’s up to them to produce the vile, lowdown conspirators.

The finger of suspicion points strongly, it is said, towards a well—known “captain of industry” as the instigator of the “plant” and to three or four local men as the tools in the matter.

Before many days had passed, the residents of Lawrence were so thoroughly alive to the methods employed by the private detectives, that the mere discovery of dynamite was enough to lay any one of them open to suspicion.

—————

[Emphasis added.]

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

SOURCES & IMAGES

International Socialist Review

(Chicago, Illinois)

-March 1912

https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v12n09-mar-1912-ISR-gog-Corn.pdf

See also:

Tag: Lawrence Textile Strike of 1912

https://weneverforget.org/tag/lawrence-textile-strike-of-1912/

The Survey

Journal of Constructive Philanthropy

Charity Organization Society of the City of New York, 1912

(search: lawrence)

Note: choose page 1690 for article referred to above.

https://books.google.com/books?id=FvUh3_L-yTQC

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~