———-

———-

Hellraisers Journal – Sunday April 4, 1909

John Murray on the Horrors of the Private Prisons of Diaz, Part I

From the International Socialist Review of April 1909:

—–[Part I]

S soon as we were alone at the end of the pier breasting the Vera Cruz harbor, the little, pock-marked secretary of the revolutionary group pulled from his pockets a piece of grey stone and held up before my eyes.

“Look at that!”

I took the fragment from his slim, brown fingers and turned it over curiously. It was a piece of coarse, grey coral.

“See! It’s porous. Now do you understand? The whole prison’s built of it.”

With an upward jerk of his hand he leveled an accusing finger at the white-washed walls of the fortress-prison shining in the sun across the waters of the blue bay.

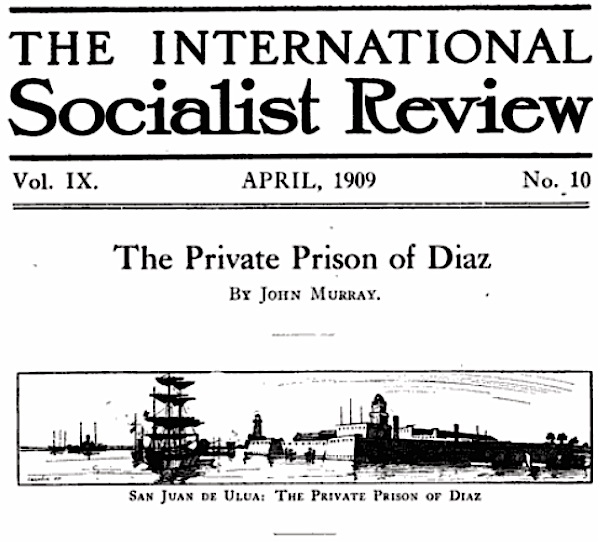

“There it stands! On that island, yonder! San Juan de Ulua! The foulest spot in all Mexico—Diaz’ private prison for his political enemies!”

The corners of the man’s mouth drew down into a snarl and his eyes narrowed to burning slits of hate as he gazed in the direction of the fortress.

Crammed in its wet dungeons below sea-level are men whose only crimes were to speak openly against the dictator of Mexico. Among them are scholars, editors, mechanics, such men as young Cesar Canales and De la Torre, Ulgalde, Marquez, Serrano, Martin, and many others, educated, refined, dreamers of a free Mexico. They played the game to the end, bravely, and now are penned like rats in the sewer-cells of the Republic’s most deadly political prison.

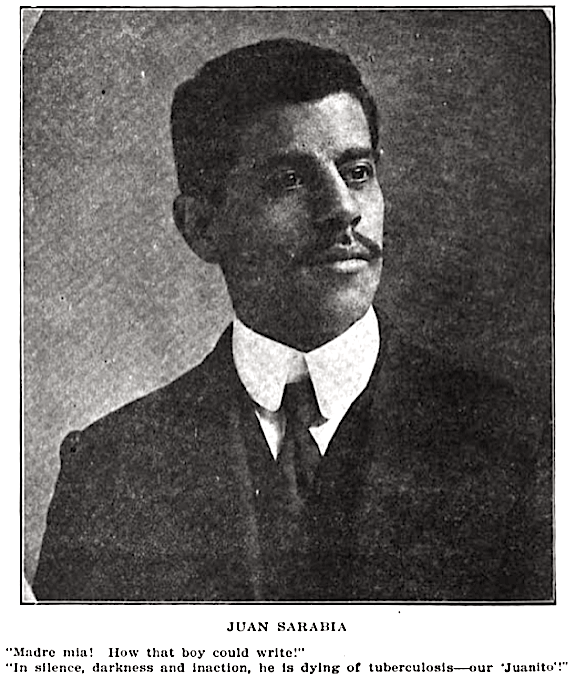

Juan Sarabia! He lies there, too, in the deepest, blackest pit of all, a coffin-like hole cut in the solid rock and called by the jailors ‘Purgatoria.’ Gentle Juan Sarabia, whose fearless pen gave Diaz no rest until he had smothered him in Ulua.

Drop by drop the salt water oozes through the coral rock of his cell and stands in pools upon the floor. And it has done its work, for the last message that we received from the inside said that Sarabia was spitting blood.

The passionate love for his imprisoned comrade shone liquid-like in the secretary’s black eyes.

Madre mia! How that boy could write! Sarcasm! No wonder that Porfirio Diaz called him the “Scorpion.” With us, Juan Sarabia was so sweet- tempered and lovable that no one ever thought of calling him anything but “Juanito.” I have seen him at headquarters writing—writing—with Rivera’s little baby, “Cuca,” asleep in his lap. And cool! When the police made their first raid on our paper, “Excelsior,” they broke into the room, front and back, just as he was adding the last paragraphs to an editorial. Several of us were standing around waiting for him to finish. As the door swung open with a crash, “Juantio” looked up and caught sight of the blue uniforms entering the room. With a quick motion of his left hand he gathered us all close around him so that he was hidden at his desk. The “Scorpion’s” pen raced over the paper. The editorial was finished and passed to a friend, who hid it between the leaves of an evening paper. Then, content, “Juantio” turned calmly to the police men and held out his wrists for the shackles.

Every one was arrested, even the bearer of the precious newspaper, but as the man left the room he tossed it aside, right under the eyes of the police, as if he had no use for it. On our arrival in the prison we sent word through friends to recover the hidden editorial. Next day, the “Tears of a Crocodile,” a biting screed aimed at President Diaz, was in print and scattered over the city, a copy even being smuggled to Sarabia in the prison “Belen.”

When he was nineteen, Juan Sarabia joined the Liberal Party in the City of Mexico and in a week he was arrested for writing an account of Porfirio Diaz’ dealings with Pearson, the millionaire English contractor, better known as “Diaz’ Partner.” After his release he was associated with our great leader, Magon, on “El Ahuizote,” a comic anti-Diaz paper rich in sarcasm, and was put in jail for eight months. But nothing could stop him and he continued writing, secretly, from the inside of the prison.

It is the truth when I say that Porfirio Diaz has honored no man more highly than Juan Sarabia. For the writings of “Juanito” were out-lawed in the land of his birth, and he was compelled to flee with the two Magons and Santiago de la Hoz, the other three men who were likewise regarded as literary outlaws, to the United States. There for a time he might have been safe if it had not been for his confiding nature. A Mexican officer made a pretense of being his friend and invited Sarabia across the line into Ciudad Juarez. Poor “Juanito” went, trusting this traitor.

That night the rurales got him and it was not long before he was swallowed up by those grim gates across the bay.

The speaker stopped and I heard the thump of oars in rowlocks rising from the water near us. The man at my side glanced over the edge of the pier.

“Here’s your boat,” he announced, “and Alfredo, the oarsman, is one of us. There! God be with you! May you come back safe!”

I grasped his hand, stepped into the small skiff bumping against the stone steps of the pier end, and the rower bent to his oars.

In all my journey through Mexico—taken for the purpose of probing the strength and aims of the revolutionary party, then on the eve of an uprising—nothing had seemed so hazardous as this trip to the fortress-prison of San Juan de Ulua.

Three men of my own blood, Americans, were already there in confinement. So I had been sneeringly informed by the Mexican General, Mas, as he finished reading my card of introduction from the American consul and grudgingly signed the pass admitting me to the prison. Inside my pockets were credentials to the leaders of the revolutionists in Mexico, and if these were discovered—especially that thin, closely-written sheet, dated in the Los Angeles county jail, by Ricardo Flores Magon, president of the Junta—my stay in Ulua might prove to be a long one.

The damp, sticky sea breeze, charged with bits of spray from Alfredo’s oars, slapped me in the face. I tried to talk with him, but he was close- mouthed, clam-like. Doubtless he was wise, for if there should be trouble on my landing, the less he appeared on intimate terms with me the better for his safety.

The white walls of the fortress drew nearer and nearer until the bobbing boat finally crossed into the shadow of the great round tower looming high over the southwestern corner of the prison. We were so near that I could see the iron gratings covering the openings in the masonry. A brown rat slid out of the prison sewer and scrambled over the rocks at the water’s edge. We both saw him, Alfredo and I, and both uttered the one thought, “An escape!”

As the oarsman unshipped his oars and seized hold of an iron ring let into the stones at the foot of the landing, the guard turned out—a slovenly lot in dirty-white cotton uniforms—and I sprang from the boat’s seat to the steps, mounted, and presented my pass to the sergeant. I was in San Juan de Ulua.

The prison courtyard was entered through a high archway on the north side of the fortress. Its walls were thirty feet thick and pierced on the inside with half-circle, cave-like openings leading to the dungeon below. From one of these yawning holes-in-the-wall came a long string of prisoners, followed by two bull-necked trusties with whips, in the sinuous lashes of which were plaited bits of shining metal. The prisoners’ shaved heads were thrust through ragged brown blankets of the texture of sacking, called “ponchos,” which fell over their backs and bellies barely to their knees, covering their scarred and bony bodies as scantily as a loosely worn shawl. Belts of rope bound these single garments to their waists. Their arms, legs and feet were bare. Out of the pit from which this ghastly procession emerged came a smell so vile that I turned sick and moved a few steps back, much to the amusement of the soldier standing grinning behind me.

Slowly the ragged, brown line moved across the stone-flagged pavement to a dark corner where stood a copper cauldron. It was supper time, and as one by one, the silent, bare-limbed figures passed before the big pot, a trusty, with an iron ladle in his hand, portioned out their soup into the upheld earthen cups, calling out in a droning voice the number of the prisoner served.

Cattle before their mangers, hogs at a trough, all have an expression of contentment at feeding time, but these worn remnants of humanity were so broken in spirit and terrorized with fear that they stood expressionless before their food.

And yet there were others in Ulua whose condition was still worse. Somewhere beneath my feet, down deep in the rock foundations, were the dungeons that held the Mexican patriots. The chances against my being allowed to see them were as a thousand to one. But still I would try.

I put the question to my guide.

The sandal-footed soldier at my side was startled, for who could be so ignorant of Mexican prison methods as to ask for a sight of the imprisoned enemies of Diaz?

“The political prisons? No. It is not permitted to visit them.”

“But,” I persisted, “the comandante said that I was to be shown everything.”

“And everything is everything, senor,” he made an all-embracing motion with his hands, adding with a sudden touch of bitterness that made me eye the man intently with surprise, “always excepting the politicals who are held ‘incommunicado,’ and have therefore become by order of the President-nothing.”

The secretary had told me that many of the soldiers in the garrison were sympathetic to the revolution. I risked a shot:

“And yet I hear that they are brave men?”

At first he stared at me in open-mouthed silence. He was almost a boy, this dark-skinned, black-eyed soldier of the line, clothed in a dirty-white uniform, and as yet barrack life had not hardened his features to the sullen, hopeless look common to the Diaz army. Finally his eyes kindled sympathetically and I tried another question:

“What do you know of them? Speak! I come from friends.”

He cast a quick glance over his shoulder to see if anyone was behind, and spoke under his breath:

“Who are these friends?”

Three names I knew that would move men in Mexico if there was a drop of red blood in their veins. I gave them to the man:

“Magon! Villarreal! Rivera!”

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

SOURCES & IMAGES

Quote EVD Mex Revolutionaries, AtR p2, Oct 10, 1908

https://www.newspapers.com/image/67587474

The International Socialist Review, Volume 9

(Chicago, Illinois)

-July 1908-June 1909

Charles H. Kerr & Company, 1909

https://books.google.com/books?id=Z6o9AAAAYAAJ

ISR – Apr 1909

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=Z6o9AAAAYAAJ&hl=en&pg=GBS.PA736

“The Prisons of Diaz” by John Murray

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=Z6o9AAAAYAAJ&hl=en&pg=GBS.PA737

See also:

Tag: Mexican Revolutionaries

https://weneverforget.org/tag/mexican-revolutionaries/

Tag: John Murray

https://weneverforget.org/tag/john-murray/

Tag: Juan Sarabia

https://weneverforget.org/tag/juan-sarabia/

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~