———-

———-

Hellraisers Journal – Wednesday May 12, 1909

Manuel Sarabia Tells Story of Illegal Arrest and Deportation, Part II

During the month of July 1907, Mexican Patriot Manuel Sarabia was arrested without warrant from off the streets of Douglas, Arizona, driven across the border, and handed over to Mexican rurales. We offered Part I of his telling of that event in Tuesday’s Hellraisers, and complete the story of his ordeal below.

From the International Socialist Review of May 1909:

[Manuel Sarabia Turned Over to Mexican Rurales]

It was a short, quick ride—not more than five minutes in time—when the brakes of the machine brought us to a stop. I was lifted from my seat and helped out upon the ground. A familiar jingle struck my ear. Yes, there they were—bridles and spurs—the rurales!

They pulled the handkerchief from my eyes, and my fate was before me. Armed with carbines whose barrels glinted in the moonlight, ten big-hatted rurales sat upon their ponies, in a half circle, facing me. Two of them were busy with a riderless mule. I quickly guessed what was to be his burden—my poor, unwilling body.

Quick orders passed to the men from their officer, and I was lifted to the mule’s saddle. With a piece of rawhide they bound my feet together under the mule’s belly, jerked it tight until the thongs cut into my flesh, and then mounting their horses waited the command to commence the night’s ride.

THE MAN IN THE CARRIAGE.

I had been delivered to the rurales at a small border town of a hundred adobe houses called Agua Prieta, governed by one Laguna, the jefe de policia. Standing a short distance down the street, close to the custom house, I noticed a carriage. As soon as the officer saw me securely tied on the mule, he loped his horse to the side of this vehicle and, after saluting those in the interior, received instructions which set our cavalcade in motion, the carriage leading the way.

My mule was a stubborn beast and could only be jerked into a racking trot with the aid of a stout riata which the rurale in front had bound to the pommel of the saddle. Tied as I was, not able to sit easily to the gait of the galling brute, I was soon worn to the point of agony. My pleadings with the rurales to either go at a lope or slow down to a walk, brought no response but curses, and I closed my mouth and gritted my teeth to deaden the pain.

All night, the carriage kept just a little in advance of our moving troop and in spite of my suffering I was intensely curious to know the personality of those within. Evidently some high Mexican official had charge of my capture.

In the gray of the morning, just as we were approaching the little town of Naco, the carriage drew up to one side, allowing our troop to pass. The officer saluted as he came abreast of the vehicle and someone’s head leaned from the window to observe us. I recognized him in an instant. It was Laguna, the jefe de policia of Agua Prieta. Back of him was another figure that kept half hidden. I turned painfully in the saddle and stared towards the carriage as we passed but the man behind Laguna still kept carefully out of sight. Who was it? Could it be?—I turned to the rurale at my side and spoke to him suddenly: “The General Kosterlitsky, did you know he was inside?”

The man grinned and answered glibly, “Surely, it was the General; you are much honored by his company.”

A little before six in the morning, the troop drew up in front of the Naco jail and I was lifted from my mule by two rurales. The night ride had left me so sore and weak that I could not stand, and I was bundled in onto the jail floor where I lay propped up against the wall. A little later some food was sent in to me and I ate it, as best I could, with my hands still coupled together with the steel manacles.

The friend who sent me this food has my sincerest thanks. I may never know his name, but it was a friend, that I am sure, for it is not the custom to supply prisoners with the quality of food I got that morning.

In the jail was a Yaqui Indian, and we soon began to talk. Like all the people of his persecuted race, this poor native of Sonora expected neither trial nor mercy from the Mexican government. He had witnessed the exportation of tens of thousands of his people to the slave camps of Southern Mexico and he expected to follow them. But my case was different—I was an educated Mexican—and he felt sure that my crime must be great indeed, to cause the severe treatment which he witnessed. I told him that I was a Liberal and he replied: “That must be a very great offense. I have seen some criminals but none have been treated like you.”

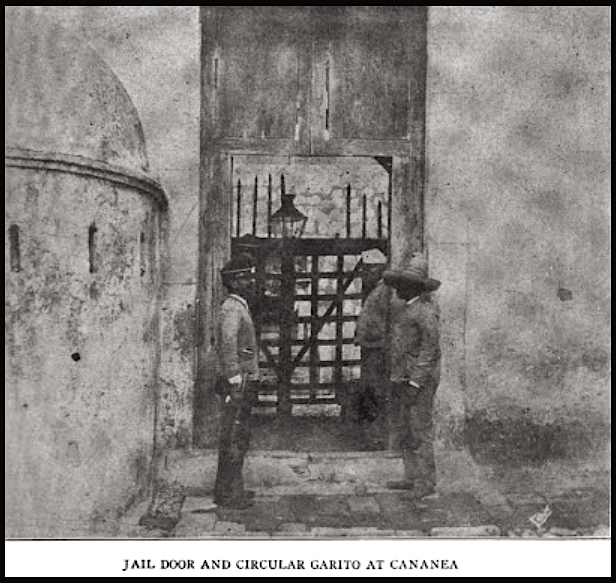

On the same morning about eleven o’clock, I was taken from the Naco jail, under a guard of twenty rurales and hurried by train to the Cananea jail, where I stayed two nights.

On the second day of my imprisonment in Cananea, one of the jailors gave me a most unpleasant piece of information. “Sarabia,” he said, “tonight the rurales are to take you to Hermosillo. It is a long, hard ride of sixty miles, through the mountains, but you will never reach that city alive as I am told that it is their intention to shoot you on the road.”

This depressed me, for such secret killing of prisoners is a common practice with the rurales. In the evening they placed me, handcuffed, on a horse, and I rode through the streets of Cananea. Was it to be my last ride? I did not know, but with the determination to make one more effort for my life I shouted out to attract as much attention as possible:

“Long live liberty—death to tyranny,” and other things which would let the passersby know that I was a political prisoner in danger of assassination by the rurales.

I believe these shouts helped to save my life, for the people in the streets stopped and listened, and the fact that I was carried away in the midst of the rurales became well known. After twenty hours of the most terrible ride through the mountains—handcuffed, and with my feet tied underneath my horse—I arrived in Hermosillo, alive certainly, but as near dead from exhaustion as I have ever been.

Many times, on this most awful portion of my trip, did I plead with the rurales to allow me to rest and to take off the handcuffs, but they had but one answer: “Tonight we are ordered to deliver you to the keeper of the Hermosillo penitentiary and tonight you must arrive—go on.”

The superintendent of the Hermosillo penitentiary had known me in the City of Mexico and would have liked to have been my friend had he dared. After three days’ imprisonment without a single charge being placed against me, I spoke to the superintendent: “How is it,” I asked, “that you break the law of the land in my case? Do you not know that the Mexican Constitution states that prisoners must be released if after seventy-two hours of confinement no charge is placed against them? What is my crime? Or, if I am an innocent man, why do you not release me?”

To this, the superintendent answered, ashamed, and with eyes avoiding mine, “It is the truth that you say, but if I were to release you I would merely put myself in your place. Listen, Manuel, I did send a report to Governor Torres, asking what to do with you, but he does not answer.”

On the eighth day of my confinement in Hermosillo a great surprise happened to me. Captain Wheeler of the United States rangers walked into the prison. I could hardly believe it; I was free, and the Captain had come to take me back to American soil.

“Do you know what this affair has cost me, Sarabia ?” asked the captain of the rangers as we sat together in the train on the way north. I shook my head.

“Two hundred dollars out of my own pocket,” he continued feelingly, as if the money lost to him was the most important part of the whole affair.

I replied that I would rather pay two hundred dollars many times over than go through such a terrible trip again. I then showed him my wrists bruised and swollen with the handcuffs.

Wheeler did everything in his power to be affable to me, told me that the whole affair was a “big blunder,” that a Mexican army officer by the name of Banderas had charged me with having killed three men in Mexico, upon which he had felt compelled to order my arrest. Finally, he gave me a hint of the excitement caused in Douglas by my kidnaping. Mass meetings had been held and telegrams sent to Washington demanding that the authorities take immediate action to obtain my release. I now began to understand why the Captain had been so willing to spend the two hundred dollars out of his own pocket to hasten my release. Wheeler also recounted his interview with Governor Torres, who acknowledged, upon the Captain putting the question directly to him, that I was not a murderer, but “only a revolutionist that was giving a great deal of trouble to the Mexican government.” The Governor, said Wheeler, expressed surprise and sorrow that I had been kidnaped and immediately wrote an order for my release.

All this only confirmed my belief in the hypocrisy of this Mexican official, for the Governor was well aware of all that had happened long before Wheeler appeared in Hermosillo.

Wheeler had been quick and willing to agree to my arrest but his slowness in returning me to Douglas was remarkable. I could have easily arrived there on the 13th—as my friends expected—but no, the Captain insisted that I stop over night at his home in Naco, thereby disappointing the people who had arranged a public reception for me in Douglas. It was Wheeler’s policy, no doubt, to allow this “international episode” to be forgotten as soon as possible.

As soon as the train bearing Wheeler and myself arrived at Nogales, the first station on American soil, two American police officers entered the car and began conversation with me. One of them I had seen in Bisbee, and the other came from El Paso, Texas. Both of them told me how glad they were to see me return to the United States, but both advised against my taking any legal action to convict the men who had helped to kidnap me.

On my arrival in Douglas, I was surprised and pleased to see a large crowd gathered at the depot to greet me, some of them carrying banners on which was written, “Welcome, Justice, Liberty.” When I alighted from the train, my friends fairly carried me to a platform arranged in the street, where I was asked to say a few words to the gathering.

But the most surprising thing of all was the behavior of two men, employes of the Copper Queen Company, who offered me three hundred dollars and a ticket to any place where I might wish to go, if I would only leave Douglas immediately.

One of them, Gallardo by name, said that all I need do was to go to the Copper Queen store and the money and ticket would be immediately given to me. These offers I declined, judging rightly the source from which they came and the reason for this sudden desire to “assist” me out of town.

Antonio Maza, the Mexican consul, had his agents continuously following me, urging that I take the money at the Copper Queen store and leave town. Finally, I told them flatly that I would not, but on the contrary, I would assist the legal authorities in bringing the kidnapers to justice—but this, unfortunately, has never yet been done.

The grand jury met in Tombstone; I went there and testified to all that had happened—but nothing was done. Many police officers were present, from Bisbee, Naco, Douglas and other places, and also the Mexican consul, Maza—and yet nothing was done.

———-

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

SOURCES

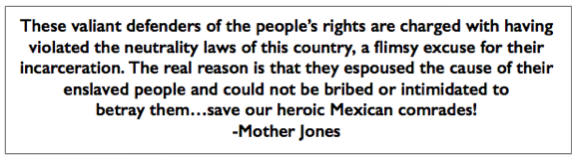

Quote Mother Jones Save Our Mexican Comrades, AtR p3, Feb 20, 1909

https://www.newspapers.com/image/66981674

The International Socialist Review, Volume 9

(Chicago, Illinois)

July 1908-June 1909

Charles H. Kerr & Company, 1909

https://books.google.com/books?id=Z6o9AAAAYAAJ

May 1909 – ISR Vol IX, No 11

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=Z6o9AAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&pg=GBS.PA833

“How I was Kidnaped” by Manuel Sarabia

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=Z6o9AAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&pg=GBS.PA853

Part II: “It was a short quick ride…..”

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=Z6o9AAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&pg=GBS.PA856

IMAGES

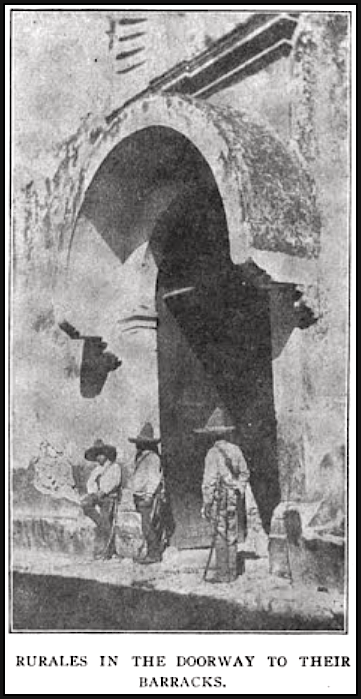

Rurales Barracks, ISR p357, May 1909

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=Z6o9AAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&pg=GBS.PA857

Gen Kosterlitsky, ISR p358, May 1909

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=Z6o9AAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&pg=GBS.PA858

Cananea Jail, ISR p359, May 1909

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=Z6o9AAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&pg=GBS.PA859

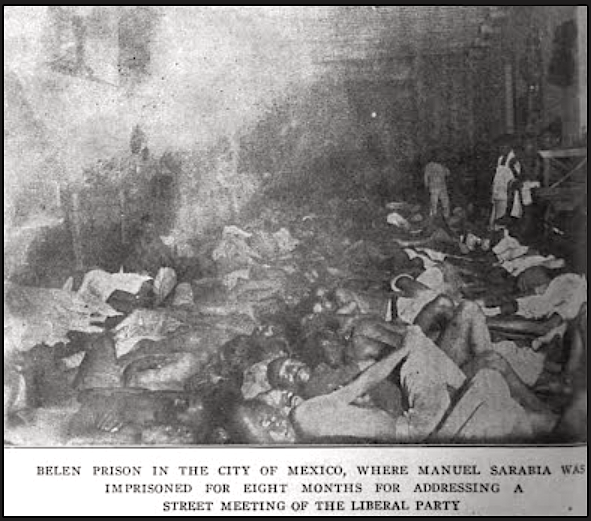

Belen Prison MX City, ISR p362, May 1909

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=Z6o9AAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&pg=GBS.PA862

See also:

Hellraisers Journal: From the International Socialist Review:

“How I Was Kidnaped” by Manuel Sarabia, Part I

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Internationale Spanish