———-

———-

Hellraisers Journal – Monday April 4, 1910

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania – “When the Sleeper Wakes” by Joseph E. Cohen, Part II

From the International Socialist Review of April 1910:

—–

[Part II of II.]

On February 23rd, Mayor Reyburn dispatched a telegram to Governor Stuart, asking for the state constabulary, or cossacks, as they are more popularly known. Four companies of them, 158 men all told, arrived next day and remained until March 1st.

Now, the people of Philadelphia had no particular quarrel with the state constabulary. Their antipathy was confined largely to the transit company and its strike breakers. To fight against the cossacks meant to engage in bloody warfare, not with fists or bricks, but guns, and this the people were not prepared to do. Were it otherwise, the handful of cossacks would never have left Philadelphia alive. So, aside from a drubbing administered to a few of their number, they were permitted to depart in peace.

—–

The people refrained from patronizing the scab-manned cars and let it go at that. Without standing upon the formality of organizing a club, they began to walk to and from work. All manner of conveyances carried passengers and did a flourishing business. The director of public safety tried to put a stop to the vehicle traffic by having scores of the drivers arrested and fined, for doing a transportation business without a license. But the wagons continued to go “all the way up” or “out” or “down.” To circumvent the director, they displayed legends such as the following: “Charity Wagon,” “Free Ride,” “Union Transit.” Unnecessary to add, no one was discouraged from tendering the conductor a free will offering.

—–

Here it may be inserted that the Philadelphia Rapid Transit Company did not exert itself to any extent in this struggle. It imported strike breakers, true enough, issued conflicting statements as to its strength, and parleyed with its old employes in the hope of bribing them to return to work. It converted its car barns into stables for the horses of the constabulary and mounted police, and tendered the use of the floors of its cars to the policemen for sleeping quarters. That represents the limit of its capacity to cope with the situation.

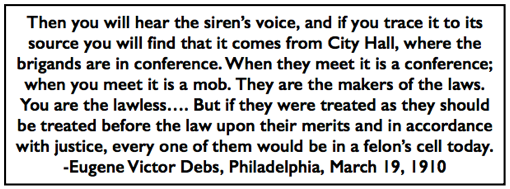

The fight upon the car men’s union and the sympathizing public was not conducted from the offices of the company. The seat of war was at the city hall. The plans of campaign were mapped out at the desks of the mayor and director of public safety, and carried into effect through orders issued by them.

Every car contained from one to half a dozen policemen, to protect the strike breakers and assist them in learning the route. Possibly ten thousand extra policemen were sworn in altogether, recruited by the political ward heelers. Their character can readily be imagined. They were called “brownies,” and seemed to aspire to become of the hue of the “black hundreds” of Russia. Whatever other faults they may have had, they early acquired a very exasperating one of clubbing and shooting inoffensive wayfarers. Of the number, three thousand or more were “plain clothes men,” who circulated among the crowd. At least two instances of dynamiting they were responsible for. To what extent they instigated disturbances cannot, of course, be ascertained. Insofar as the mayor and director were concerned, it was a fight of brute force, in which the side guilty of the greater amount of thuggery would prevail.

The local magistrates and judges were at the elbow of the company’s officials. The term “riot” was distorted out of all legal sense, while an amusing precedent was established in making it appear that the alleged act of one individual, C. O. Pratt, constituted a “conspiracy.”

It is hardly worth while to enter into a consideration of the part played in the trouble by the mayor and his underlings. Pennsylvania’s political history, and Philadelphia’s contribution to that history, are too well known to require it. Suffice to mention here that after the mayor frowned down all talk of arbitration, he called the attention of the city councils to an act of assembly of 1893, which provided a way for the adjustment of grievances between, employer and employe, by having each side select three arbiters, the common pleas court appoint three, the nine to constitute the board. And after doing that, when the men on strike offered to accept this medium, unfair to them though it was, the mayor sitting on the board of directors of the company, as a representative of the city, voted against his own proposition.

That the mayor of the city owns traction stock is denied. But is has been charged, and never refuted, that the director of public safety is a heavy holder and a heavy loser. During the course of the strike stocks tumbled headlong down, so the rage of the director can be understood.

Like most, if not all, public service corporations, the Philadelphia Rapid Transit Company, apart from its stock manipulations and gentle manly “steals,” has been enriched by valuable franchises and other favors conferred upon it without a penny of recompense to the city. Transit and political interests have always been found together. Therefore, no stone has ever been left unturned to defend the holdings of the clique in control of the company at any particular time.

To cement the tie between the corporation and the city officials, a contract was entered into by city councils in July, 1907, whereby the company bound itself to turn over to the city all earnings above a stipulated amount; the city, in exchange, to be the guardian of the company. To insure the carrying out of the provisions of the compact, the city is entitled to three representatives on the company’s board of directors. That the city’s representatives served the company only too well, is attested by the fact that one of them has since been promoted to the vice-presidency of the company, while another openly fought the public in the strike. The mayor’s position we have already seen. On the other hand, no part of the company’s surplus has ever found its way into the city treasury.

Among the holders of large amounts of traction stock are men who either own or influence one or more of the daily papers. This explains why every editor opposed the car men, although several of them went as far as they could in antagonizing the present directors of the company. Financial jugglery even reached the stage when it was believed that the men in control aimed to throw the company into the hands of a receiver, in order to squeeze out the small investors. As many as 25,000 shares changed hands in one day’s transactions during the strike.

That the group of financiers seeking to discredit the present directorate desires not to stand in intimate delations with labor was shown later on when the president of the Central Labor Union, John J. Murphy, was arrested on the charge of “inciting to riot.” His unsophisticated friends hastened to try to procure bail from the moneyed men who had supported the reform movement, on whose ticket Murphy had twice been a candidate. But the eminently respectable reformers refused to have their names sullied by association with that of a strike leader.

—–

One more incident might be cited here to indicate the nature of the conflict. Among those who put in a conspicuous appearance were the United Business Men’s Association, claiming to speak for 90,000 of the city’s merchants. They reported themselves to be “the bone and sinew of the community.” But they and their plea for arbitration received scant courtesy from either the company or the city officials. A delegation from the Kensington Business Men’s Association came down to attend a session of the city councils and exercise their influence upon that recalcitrant body. They were permitted to have their picture taken in front of the city hall, but not to enter the portals of that stately edifice. In this way was it made manifest that the fight was between the real vested interests, corporate wealth, in the one camp, and labor, the small business men and all other elements of the people, in the other.

For their own part, the car men’s union, if anything, under-estimated their relative strength, and guided themselves accordingly. Everyone strained himself to the utmost. The two local secretaries scarcely left headquarters, day or night, while other local officers and international officers, after attending to matters in the office during the day, were out all hours of the night and early morning, addressing meetings called for the members of a car barn, some sister union or the public.

The car men are fully aware that the company has plenty of resources, that it is strongly intrenched politically, and that the greater part of the financial burden of the fight will be borne by the city. For this reason, among others, all that the men hoped to accomplish was arbitration, arbitration that would secure for the men a fair consideration of their grievances.

At the same time, the riding public had its own complaints against the company, although it had apparently never entertained any serious idea of having them attended to. Yet it was on the lookout for the occasion to present itself where it could manifest its displeasure at having the rate of fare increased although the service remained abominable. Furthermore, that which had been the eye-sore of the company, the big buttons worn by the members of the union, had done much to encourage a fellow feeling among the working people who daily came into contact with the motorman and conductor. So that the notion of having a sympathetic strike, as a protest against the management of the company and the executives of the city, was not the extravagant conception of some dreamer. It was the expression of the desire and will of the working people of the community.

On Sunday afternoon of February 27th, two meetings were held in the halls of the United Trades Association. One consisted of the delegates to the Central Labor Union; the other of representatives from unions unaffiliated with the central body. The meetings lasted all afternoon. Every one present at those meetings—and there were a dozen international officers and several veterans of the labor movement—everyone declared it to be the most inspiring meeting he had ever witnessed. There was unanimity of opinion as regards the purpose of the meeting. But the unaffiliated unions were in favor of carrying out that purpose the following Tuesday. They had to be prevailed upon to withhold making the move until Saturday.

In the anteroom were nearly a hundred newspaper men, one local paper having as many as fourteen reporters there. After what seemed endless waiting, the union’s press committee came with the resolutions, with a list of the organizations which had participated in the meetings, and with words of greeting from unions in other cities. By relays the information was scribbled down and telephoned to the paper offices. Within a quarter of an hour the news was in type and had been telegraphed across the continent.

The first general strike in America [*] had been ordered. Philadelphia, the city that seemed until that hour to be impervious to all progressive ideas, had for once taken the lead. The sleeper had awakened!

Within the next few days special meetings were called of all unions and the question of going out on strike was put to a vote. With the exception of a few organizations bound up in “iron clad contracts,” the decision was favorable. Wednesday evening there was held a joint conference of delegates from all unions in the city, whether or not affiliated with the Central Labor Union. A proclamation was drawn up, a committee of ten empowered to take command of the situation, and the call to cease work issued for Friday midnight, March 4th.

A very curious thing happened at this juncture. The company furnished the newspapers with copies of telegrams it had received from manufacturers’ associations and citizens’ alliances throughout the country. With two exceptions, they were dated March 4th. It demonstrates only too well the concerted nature of the action of the employers. It showed that it was recognized among the ruling class that this was to be an important grapple between the forces of labor and capital.

Possibly the publication of this intelligence was calculated to dismay organized labor. In this purpose it utterly failed. At the appointed hour the general strike went into effect.

Philadelphia, Pa.

(To be continued.)

*Note: The Philadelphia General Strike was not the first; previous city-wide general strikes include: 1877-St. Louis and 1892-New Orleans.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

SOURCES & IMAGES

Quote EVD, Lawmakers Felons, Phl GS Speech, IA, Mar 19, 1910

https://www.marxists.org/archive/debs/works/1910/100319-debs-fighttothelast.pdf

The International Socialist Review, Volume 10

(Chicago, Illinois)

-July 1909-June 1910

C. H. Kerr & Company, 1910

https://books.google.com/books?id=MVhIAAAAYAAJ

https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/009034160

ISR of Apr 1910 & Article by Cohen

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=MVhIAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&pg=GBS.PA865

Part II

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=MVhIAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&pg=GBS.PA870

History of the Labor Movement in the United States, Vol 5

The AFL in the Progressive Era, 1910-1915

-by Philip S Foner

International Pub, 1980

-see Chapter 6, page 143

https://books.google.com/books?id=vIn-bO2Oe1cC

See also:

Tag: Philadelphia Street Car Strike of 1910

https://weneverforget.org/tag/philadelphia-street-car-strike-of-1910/

Tag: Philadelphia General Strike of 1910

https://weneverforget.org/tag/philadelphia-general-strike-of-1910/

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Which Side Are You On – Dropkick Murphys

Lyrics by Florence Reese

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Which_Side_Are_You_On%3F