———-

———-

Hellraisers Journal – Tuesday October 4, 1910

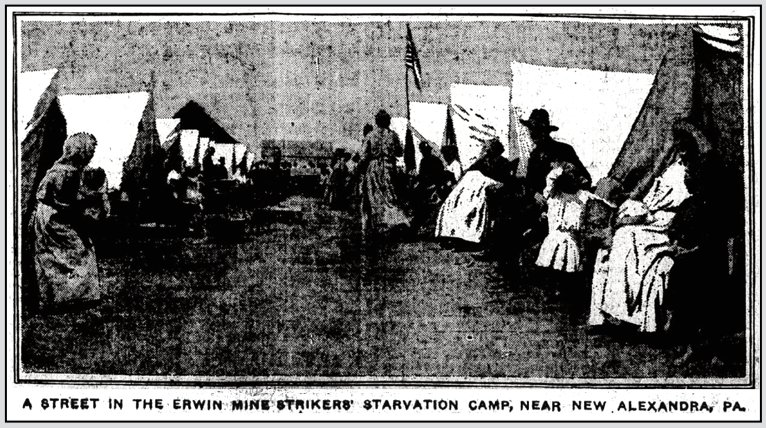

Irwin Coal Field, Pennsylvania – Report from Strikers’ “Starvation Camp”

From the Duluth Labor World of October 1, 1910:

Keystone State Awakens to Hunger-Driven Peonage

Practiced Within Its Confines

PITTSBURG, Pa., Sept. 30—Thousands of Pittsburg women, influential club women as well as the wives of storekeepers and mechanics, are signing a petition to Governor Edwin S. Steuart asking that he intervene and compel the coal companies to arbitrate the strike in the Erwin [Irwin] and Greensburg coal fields.

Piloted by the “Angel of the Camp,” Miss Emmeline Pitt, committees from various women’s clubs have visited the frail tents in which are huddled the thousands of miners’ wives and children, and, after hearing the stories of eviction and brutality committed by the deputies, have gone back to their organizations burning with indignation against the coal barons and determined to force action from the state authorities.

[Asserts Francis Feehan, president of district No. 5:]

The operators could settle this strike, settle it and give the miners all that they demand and then operate their mines at 20 per cent less than it is costing them now. It’s the strike-breakers that cost. They’re paying them $2.50 and $3 a day with rations—and that’s more than the skilled union miners ask.

Experienced miners say that the United Coal company is paying at the rate of $3 a ton to have its coal mined, while the market price is just half that amount.

Three things the striking miners want:

1. Recognition of the union.

2. Check-weighmen on the tipples.

3. Payment of the Pittsburg Scale.And these three things the miners will win, coal barons or no coal barons, for the entire power of the United Mine Workers of America is gathering behind them.

————

GAUNT MOTHERS, THEIR BABES STARVING, HERE

——-Special Correspondence of Labor World.

NEW ALEXANDRA, Pa., Sept. 30.—Three hundred puny babies, thinly clad and underfed by half-starved mothers who have nothing to give, live beneath canvas roofs and within canvas walls these chilly days and shivery nights in the Erwin coal regions of western Pennsylvania.

A thousand other little children, barefoot and almost barebacked, “live” on bread and water in that starvation camp among the foothills of the Alleghenies.

Five thousand women suffer grief and hunger among their starving little ones, but bravely encourage the despairing men—10,000 fathers, husbands and sons—who refused last March to be slaves in the mines of the Erwin district operators any longer and who are desperately sticking to the resolve made then.

For weeks these men and women and children, driven from the company houses that were their homes to tents on the unused hillsides, have lived on berries principally. The chill nights of September have brought a refreshing, if not over-nourishing change. They now have mushrooms with berries. And when the union committee distributes the pennies of its relief fund, they have a little of bread, too, although most of it is saved for the children, who dip it in water—bread and water, the dungeons’ bill of fare.

In New Alexandra, in Latrobe and in Greensburg, the county seat, I found desolation, hunger, sickness, stagnated business and misery. Everywhere are empty company houses with doors and windows boarded up, eloquently telling of the homeless, condition of their former occupants, who are now living in tents. Some of the houses are occupied by strike-breakers, but many more are empty. On every empty house is a “no trespass” sign. Tiny truck gardens with vegetables rotting on the ground tell the pitiable story of the suddenness with which the striking miners were evicted by the operators two months ago.

The strike? The Labor World has already told about that. The men claimed and apparently have proven that they and their families could not live on what they were being paid last winter, so they struck. Deputy sheriffs and detectives were imported to club them into submission. There was bloodshed and terror. Men were arrested and even shot for refusing to enter the mines. But the strike is six months old, and the men as determined as ever.

It has been a hard struggle. When the tightest pinch came some of the men went back to their old homes to gather the potatoes, sweet corn and vegetables that they themselves had planted and cultivated. They were arrested for “trespassing.”

During the summer the union has been able to give a little relief—a pittance, however. The men were allowed 15 cents a day, women seven and children two. How far does 32 cents a day (for man, wife and five children) go in your house, Mr. Citizen?

Now the chilly nights of the fall up here in the foothills are upon them. It cold, often at night, bitterly so. To heat the tents is practically im possible, even if the coal barons would sell the coal to the miners, and if they had the money to buy it with. While it was too cold for me to go without my overcoat last night, I saw little children barefooted, clothed in thin, tattered summer garments, fairly blue with cold. One little fellow’s teeth chattered so badly as he told me, “I hope we can move back home soon,” that it was difficult to look at the carefully cropped lawn and palatial mansion of one of the big coal operators in the near distance with anything resembling complaisance.

The father of a family, himself in ragged garments, with tears in his eyes, said:

I can’t see my wife and our babies starve and freeze, I would willingly go back into the mine to save them, but they are not the ones at stake.

It’s the lives and comfort of all. If we go back now, all is lost. For 20 years I have worked in that mine there, and never once have I had enough to eat and wear. If I and the rest go back now, it will mean 20 more years of the same slavery.

In front of a tented home I saw a tired, pale mother doing the family’s washing.

[She said:]

Oh, I don’t mind it so much, but the little ones is what is worrying me. We can’t buy shoes for them. Their clothes are last year’s and they’re mostly holes. It has been hard all summer, and it is getting worse every day. Every night the children cry because they are cold, though I give them all the bed covering we’ve got. And when I think that winter is coming on, my God! I don’t believe we can live through it.

But she would not listen to her husband’s going back to work in the mines under the old conditions.

While the miners’ families are suffering from cold, hunger and sickness, the coal barons refuse to arbitrate. Marcus Sexton, treasurer of one of the larger coal companies and virtual head of the operators’ combine, told a committee of strikers:

“There is nothing to arbitrate. The coal mines are here. You can start to work tomorrow if you wish. We own the mines and you own your labor. The wages we will pay is what we want to give you and not what you think you ought to get.”

[Emphasis added.]

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

SOURCES & IMAGES

Quote Mother Jones, Brutal Ruling Class, Cnc Pst p7, May 31, 1910

https://www.genealogybank.com/

The Labor World

(Duluth, Minnesota)

-Oct 1, 1910

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn78000395/1910-10-01/ed-1/seq-1/

See also:

Tag: Westmoreland County Coal Strike of 1910–11

https://weneverforget.org/tag/westmoreland-county-coal-strike-of-1910-11/

The Labor World

-June 4, 1910

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn78000395/1910-06-04/ed-1/seq-1/

-June 18, 1910

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn78000395/1910-06-18/ed-1/seq-6/

-Sept 17, 1910

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn78000395/1910-09-17/ed-1/seq-1/

-Sept 24, 1910

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn78000395/1910-09-24/ed-1/seq-1/

For more on Emmeline Pitt, see:

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/search/pages/results/?state=&date1=1910&date2=1963&proxtext=%22emmeline+pitt%22&x=17&y=16&dateFilterType=yearRange&rows=20&searchType=basic&sort=date

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The Coal Miner Song – Jimmy Joe Lee