—————

—————

Hellraisers Journal – Monday February 12, 1912

New York, New York – Children of Lawrence Strikers Welcomed by Socialists

From The New York Call of February 10, 1912:

From The New York Times of February 11, 1912:

150 STRIKE WAIFS FIND HOMES HERE

—————

Great Throng Waits in Cold to Give Warm

Welcome to Children from Lawrence, Mass.

———-BANNERS OF RED WAVE

———-

And Crowd Sings the Marseillaise–Children Answer with Strikers’ Cry

–Homes Offered to Many More.

———-The Grand Central Station was the scene of a great demonstration last night when 150 boys and girls, ranging in age from 2 to 12 years, arrive here from Lawrence, Mass. They are the children of the striking textile workers, and they come here to be cared for by working people of New York, who have promised to feed and house them until peace has been restored in Lawrence and the great mills there are again in operation.

More than 700 persons applied for one or more of the children. Among them, it is said, were Mrs. O. H. P. Belmont, Miss Inez Milholland and Rev. Dr. Percy Stickney Grant. The children, however, were all given into the care of the families of laboring men or members of the Socialist Party.

To greet the children a crowd of 5,000 men, women, and children packed the Grand Central Station concourse, singing the “Marseillaise” in many tongues. They waved red flags, some with black borders, and all bearing Socialistic mottoes. It was noticed that not one in that crowd waved aloft the Stars and Stripes.

The men that waved the big red flags said they were not anarchist but Socialist flags, but, whatever they were, they were red everywhere except the lettering and the black borders. The black borders, it was said, were marks of mourning for those of the strikers who have lost their lives in Lawrence. Besides the flags, there were banners, also red, on which were displayed in big type what the crowd called “mottoes.” One painted in gold letters on a long, red streamer, read:

Ye exploiters, kneel down before the of your victims.

Another banner announced that the “libertarians of New York affirm their solidarity to the strikers of Lawrence.” Still another banner bore the same message, except that instead of “libertarians,” it read “the Liberians of New York,” &c. There was also another flaming piece of bunting on which was painted the information that certain Harvard students favored “a free country.”

Long Wait For the Children

The train on which the children were expected to arrive was due at 3:30 P.M., but it was an hour late, and it came in without any of the Lawrence Children. When it did roll in a brass band was playing in the concourse, and the crowd was lined up against ropes that were stretched for the purpose of preventing a too hearty welcome being given to the children.

The crowd did not understand why the children were not on the 3:30 train, and so great did the excitement become that the police had an inquiry made all along the New Haven line to Boston. It was learned that the children missed their train in Boston, and it was announced from the bulletin board that they would arrive on the train that was due at 5:42 P.M., but which would not get in until 6:50 P.M.

It was about 4 o’clock when the unwelcome information was bulletined and the crowd, which had stood for two hours in the bitter cold waiting for the train, dispersed to gather again about 6 o’clock in still greater force. At 6:30 P.M. the Grand Central concourse was packed to capacity, and the reserves of the East Fifty-First Street Station formed lines behind which the crowd was forced to stand until after the children had come out of the station.

At 6:50 the searchlight of the electric engine that pulled the train from Highbridge was sighted coming into the train shed. Then the excitement started in earnest. Slowly the hum of the “Marseillaise” started, gradually gathering in volume. It ended when the train came to a stop and then ensued a series of frantic shouts and yells in a dozen languages. In all the medley there was not heard a single English word except the sharp commands of the police and the station men who were assisting.

Announce Themselves as Strikers

Orders had been issued that the children were not to leave the train until the other passengers had left it and were safely out of the shed. When the children were escorted from the cars they were in charge of fourteen men and women from Lawrence, one of whom was a trained nurse. The children were formed in columns of twos, and at a signal from a young man who was one of those in charge they announced their arrival with a yell.

This is the way the yell goes, and the children shouted it all the way out of the station:

Who we are, who are we, who are we!

Yes we are, yes we are, yes we are.

Strikers, strikers, strikers.

The enthusiasm seemed to be contagious, and even the children under 5 years of age caught it and forgot about the cold. Outside the gates and behind the ropes the men and women and the children who had gathered to welcome the little ones yelled and yelled and when they got tired of yelling they jumped up and down and threw their hats and caps into the air. They could see the children coming down the concrete platform that extends along the tracks, and the nearer the tiny visitors got the greater the demonstration became.

The task that confronted the police was no easy one, for they had to keep open a passage wide enough for the children, and besides see that none in that cheering crowd got near enough to show with a hug or kiss how glad he or she was that the children had come. The police acted kindly, but firmly. Few in the crowd understood what they said, and that was why they sometimes used their hands to push them back, in a firm but never in a brutal way.

Now and then some man would pass holding a wee child in his arms, one of the visitors too young to stand that walk in the cold that the older and lustier-lunged youngsters appeared to enjoy.

Welcomed and Fed at the Labor Temple

The crowd formed in behind the youngsters and followed them out into the street, where the line again formed. This time the men carrying the flags and the banners going ahead, with the children forming in behind them, and then the rest of the thousands. Through Forty-third Street to Third Avenue and then down that avenue to the elevated station at Forty-second Street the line of march extended. There the children were taken on Elevated trains to Eighty-fourth Street, where they left the trains to go to the Labor Temple at Eighty-fourth Street and Second Avenue, where another crowd waited to welcome them.

The Temple, big as it is, was not half large enough to accommodate the throng that wanted to get in and take part in the welcoming ceremonies. Every hall and every room, and there are many of them in the Temple, was packed to the doors, while on the stairways the people were jammed from rail to wall. One lone special policeman had the task of opening up a way for the children. How he did it is a mystery, but somehow the children got to the room where a warm meal, prepared by the Workman’s Educational Association, was ready for them.

The hungry children did not need any instructions about disposing of that meal. They ate and ate until they couldn’t eat any more, and then a place was found to seat them while those who are to care for them got ready to take them to their homes.

The distribution required several hours and many of the children were sound asleep before they were assigned to anybody by the Woman’s Committee of the Socialist Party, who had charge of the placing of the children.

The hour became so late that many persons took five and even six children temporarily and a further distribution will be made to-day. Dr. James P. Warbasse of 386 Washington Avenue, Brooklyn, took away six little children in his automobile. He said he would keep several, and had friends who would care for the rest. Dr. G.S. Gibbs of Balston Spa, N.Y. also took six children. Most of them were distributed among the members of the families associated with the Socialist Party, and the Industrial Workers of the World. It was said that the requests of Dr. Grant and Mrs. Belmont may in part be granted later.

All the children stood the trip from Lawrence to New York in fine style, and not one among them showed any ill-effects from the long journey.

The children are of various nationalities, principally Lithuanian, Polish, Portuguese, Italian, and French. All of them, however, speak English, and they are as a rule a fine- looking, and, despite the present condition of the parents, a healthy looking lot. They were poorly clad and few had overcoats or cloaks. Many of the smaller ones had sweaters and wore woolen scarfs wrapped around their heads.

Those who had charge of the reception and distribution were Mrs. Elizabeth Gurley Flynn; the Socialist speaker, who has been addressing the strikers in Lawrence: Mrs. Margaret Sanger, J.A. Jones, Raimondo Fazlo, and Leonardo Frazini.

Had the children arrived at 3:30 P.M. as expected, the plan was to march them through the streets to Union Square where there was to have been an open air demonstration of sympathy and support for the Lawrence strikers. When it became known that it would be dark before the children arrived, that part of the programme was abandoned. Later in the week the children will probably take part in one or more meetings that are being organized in behalf of their striking parents.

The bringing of the children to New York is the result of an invitation extended by the New York Lawrence Strike Committee, and it is said that another train load will come this week. It is a new departure in strike management in this country, but has been used successfully in France and Italy.

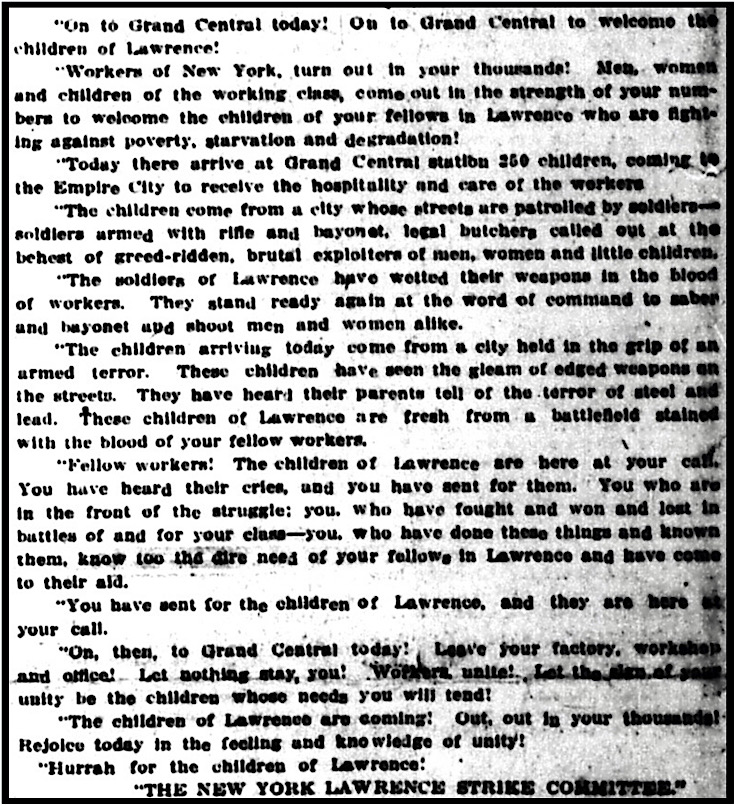

In a notice sent out to “the workers of New York,” the New York Lawrence Strike Committee says of the coming of the children:

The children come from a city whose streets are patrolled by soldiers-soldiers armed with rifle and bayonet, legal butchers called out of the behest of greed-ridden, brutal exploiters of men, women, and children.

The soldiers of Lawrence have wetted their weapons in the blood of workers. They stand ready again at the word of command to sabre and bayonet and shoot men and women alike.

The children arriving to-day come from a city held in the grip of an armed terror. These children have seen the gleam of edged weapons on the streets. They have heard their parents tell of the terror of steel and lead. These children of Lawrence are fresh from the battlefield stained with the blood of your fellow-workers.

Fellow-workers! The children of Lawrence are here at your call. You have heard their cries and you have sent for them. You who are in the front of the struggle; you, who have fought and won and lost in battles of and for your class-you, who have done these things and known them, know too the dire need of your fellows in Lawrence and have come to their aid.

You have sent for the children of Lawrence, and they are at your call.

[Emphasis added.]

—————

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

SOURCES & IMAGES

The New York Call

(New York, New York)

-Feb 10, 1912

https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/the-new-york-call/1912/120210-newyorkcall-v05n041.pdf

The New York Times

(New York, New York)

-Feb 11, 1912, pages 9+10

https://www.newspapers.com/image/26045890/

https://www.newspapers.com/image/26045908/

See also:

Tag: Lawrence Textile Strike of 1912

https://weneverforget.org/tag/lawrence-textile-strike-of-1912/

Tag: Lawrence Textile Strike Children’s Exodus 1912

https://weneverforget.org/tag/lawrence-textile-strike-childrens-exodus-1912/

“The Lawrence Strike” by Mary Heaton Vorse

Published: A Footnote to Folly: Reminiscences of Mary Heaton Vorse, Farrar & Rhinehart, 1935.

Transcribed: for marxists.org in January, 2002.

https://www.marxists.org/subject/women/authors/vorse/lawrence.html

PART I:

ONE COLD afternoon in the winter of 1912 I went with Joe O’Brien [husband of MHV] to meet the children of the Lawrence strikers in the temporary building of the Grand Central Station. We had been finding homes for them all the past week. Waiting groups of people carried banners: “Welcome to the Strikers’ Children” — “Local 29, Ladies Garment Workers, Welcomes Lawrence.”

The train didn’t come; people got restless. The workers began milling around. Bill Haywood had telegraphed Socialist head-quarters and the Call that the children would be in on the three o’clock Boston Express. It was after four and there had been no word from the children. Everybody was grumbling. Dolly Sloan ran around saying,

“Where’s the man with the permit to parade? He’s down at the Proletario office reading Salome. That’s the matter with the radical movement. The man with the permit to parade is always off in the Proletario office reading Salome.” By this time the police were beginning to look suspiciously at the crowds of workers with red banners. Some wit made a placard: “This Is a Free Country. Harvard Students.”

A march around the station began, a red flag fluttering at its head. The placard — “This Is a Free Country. Harvard Students” — preceded it. There was a stir of excitement and gaiety. The police didn’t know what to do. These young men might be students, after all. Better leave the red flags alone. What a laugh on them if they were to arrest Harvard crimson.

You could tell a good deal about the state of the labor movement in 1912 by looking over the waiting people. They represented dozens of locals and scores of trades. All sorts of people had come to meet the strikers’ children. Socialists and anarchists, liberals and syndicalists and plain trade unionists. There were A. F. of L. locals, who, even if they disapproved of dual unionism, were looking with sympathetic eyes on the Lawrence strikers and felt that the United Textile Workers under Golden had played a shabby part in Lawrence.

There were many Socialist locals represented. There were bands of “Ypsls,” youngsters from the Young People’s Socialist League; delegations from the Food and Restaurant Workers, which was at that time a militant union with syndicalist leanings. There were Italian locals, people from the Needle Trades, delegations from Knit Goods Workers. Some of these had big boxes filled with red mittens, gifts from the workers to the children.

It was cold in the station. People stamped their feet. Groups of people huddled together, grumbling. It was dusk and the air up above looked blue. Shafts of light pierced through the building. One looked out on trains puffing in and out through an intricate forest of pillars.

At last Joe O’Brien and I went for a cup of coffee. When we got back the children had come. They had not only come, but they had gone, and we had missed them; but we followed them by the bright red mittens they had lost and left behind on the sleety pavements. The spots of red guided us like the stones of Hop-O’-My-Thumb. Here was a mitten on a snow pile, and here was another by the Third Avenue el, and another higher up the steps. The children were one train ahead of us. A red mitten flagged us on the uptown station where they had got out to go to a dinner prepared for them by the Hotel and Restaurant Workers. We caught up with them there.

The children were already at the tables. The air was full of the noises of a hundred young voices. Black-eyed Italian children, French Canadian children, Syrian children, blond-haired children from the Baltic States. How they chattered. How they ate. They had never had a meal like this, topped off with ice cream and cake and fruit, nuts and raisins.

Meanwhile their friends crowded around, workers helping other workers. A sudden flame of sympathy had brought unity to different groups. The New York workers were standing solidly behind the Lawrence strikers, and for proof of it these children, whose homes could no longer support them properly, through the long weeks of the strike were being looked after and cared for by other workers.

As for the children, they were off on a great adventure, and their account of this adventure in the letters they were going to write home was to be one of the high spots of the strike, one of the ways that the workers’ courage was kept aflame.

The strike had broken out not long before. Twenty thousand textile workers in Lawrence had walked out against a wage cut. It was a sudden, unplanned uprising. A fifty-four-hour week for women and children had been put into effect in Massachusetts, and the textile industry employed so many women and children that it meant a fifty-four-hour week for everyone. Consequently, there was a wage cut. It was a small cut, but it meant “four loaves of bread” to the workers.

There was almost no organization. There were less than three hundred scattered workers in the I.W.W., with another two hundred and fifty or thereabouts organized under the United Textile Workers, who belonged to the higher paid crafts such as weavers and loom fixers.

Wages in Lawrence were so low that thirty-five per cent of the people made under seven dollars a week; less than a fifth got more than twelve dollars a week. They were divided by nationality. They spoke over forty languages and dialects, but they were united by meager living and the fact that their children died. For every five children under one year of age, one died. For children under five years of age, the death rate was 176 in a thousand. Only a few other towns in America had higher death rates. These were all mill towns.

Practically all New England had grown rich on the products of textile mills, in which profits as great as those of the Pacific Mills were common. The Pacific Mills had been capitalized for only two million dollars in the beginning. The company had paid twelve per cent dividends as regularly as sunrise. In addition, it had paid thirty-four per cent in extra dividends between 1905 and 1912, and had a six million-dollar surplus over and above what it had written off against a sinking fund and depreciation. The gains of the other mills were similar.

Meantime, the labor costs were falling. Much more cloth per worker was being made, and the speed-up, which caused the out breaks in the South in 1929, was already “tentatively put into effect” by the American Woolen Company.

It was against such conditions that this spontaneous strike occurred. The workers streamed out the gates of one after another of the long mills, each moated by its canal. Strike demands were swiftly formulated:

15% increase

Double pay for overtime

Abolition of the bonus and premium system

No discrimination because of strike activity.[…..]

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Sing in Solidarity Virtual Choir: The Internationale