We think such people [Plutocrats]

ought to work for what they get.

We do not want to take away what they have,

but we want to prevent them from taking

anything more away from us.

-Big Bill Haywood

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Hellraisers Journal, Wednesday August 14, 1918

Chicago, Illinois – Haywood Takes the Stand, Part I

Report from Harrison George:

It was 12:30 p. m., [Friday] August 9, when [Defense Attorney] Vanderveer called: “Mr. Haywood.” Reporters broke for the door to release the word that at last William Dudley Haywood, termed by them “Big Bill,” and charged with being “chief conspirator,” had taken the stand in defense of himself and of the organization of which he was the General Secretary-Treasurer. In a few minutes the press table was crowded with writers and cartoonists flocking in to “cover” the story of the big man in the chair. For the major part of four hot days the big man sat there, wiping away perspiration, answering questions with that remarkable memory of his; now smiling, now placid, now and again on cross-examination overawing the petty-souled [Prosecutor] Nebeker, as his heavy voice rose in defiance against the accusers of “The One Big Union.” During those four days the spectators’ benches were full, among the crowd being faces familiar to labor. There were Scott Nearing, Anton Johanssen, “Mother” Jones, and the loved old battler, ‘Gene Debs.

Haywood reviewed his early life, a personal history, which, for lack of space, can be given here only in synopsis. He was born 49 years ago at Salt Lake City, Utah. At less than 9 years of age he went to work in a mine, working underground. He left home at 15 to work, first in the Ohio mine at Willow Creek, Nevada. Until he was 31 years old he lived the average life of the old-time western “hard-rock” man, working underground. He joined the Western Federation of Miners at Silver City, Idaho, and in 1900 was elected to the General Executive Board of that union, later becoming Secretary-Treasurer and holding that office until 1907. His first strike experience was in 1899 in the Coeur d’Alene strike, which was against a reduction in wages. A day or two after the strike broke the mill of the Bunker Hill and Sullivan mine was blown up and the operaters at once brought gunmen, and then soldiers of the regular army came. About a thousand strikers were thrown into one vile “bull-pen” and held by the militia. Many sickened and died. Miner’s wives received notice from army officers insisting that they receive negro soldiers; some of these women, going to ask for their husbands, were violated by soldiers in the presence of their helpless men. The strike wore itself out, but the wages were not cut. It was here that the “rustling card” was born.

The next strike of Haywood’s experience was at Telluride, Colorado, in 1901, over wages and hours. There the miners were well organized and told the non-union men to “join or leave the camp.” No troops interfered there, and the strike was won.

The next strike was at Colorado City over the eight hour law. The W. F. of M. had first agitated for an eight hour law after the strike of 1894. A bill applying this to mines was presented to the legislature in 1895, but the Colorado Supreme Court advised the legislature that the mining industry alone would be discriminated against in violation of the constitution. In 1899 such a law was passed, but the State Supreme Court declared it unconstitutional. In 1901 an amendment to the state constitution making provision for an eight hour law was put to a referendum and carried by a majority of 46,714 votes. Democrats, Republicans and People’s party all pledged themselves to pass the law, but legislature after legislature jockied with it, yet never passing an eight hour law. “We got the eight hour day, though, by striking for it,” said Haywood.

On July 3, 1903, the great smelter at Denver was “pulled” in strike when the metal was hot, thus “freezing” the furnaces. The great brick chimney of that smelter still stands, the highest stack west of the Mississippi, but no smoke from it has soiled the sky since July 3, 1903, and it stands as a monument to the power of the now decadent Western Federation of Miners.

Haywood told of the coal miners’ strike also, which took place to force the observance of seven state laws, one forbidding “company money” and one providing for check-weighmen. Labor ruled Colorado industrially, but never won anything by legislation.

“Labor generally has but small representation,” said Haywood, “except in the eleven “white states’, so-called. Women workers cannot vote; children workers cannot vote; and the negroes of the South are almost wholly disfranchised.” Direct industrial action is favored by all labor leaders, as it is favored, also, by employers; and Haywood cited the New York Factory Commission Report wherein Gompers spoke for direct action.

“The first clause of the Preamble is true,” said Haywood, “the wage workers are but little, if any, better off than the chattel slave of the Old South. In fact, it seems the chattel slave had some advantage over the negro wage slave of today. His body was owned by his master, but his soul was free, and that free Soul gave birth to song. There are no songs today from the negro wage slave of the south, no melody is born in the soul of the negro, no ‘Suwanee River, no ‘Old Kentucky Home.’ Today the blacks are brought to live in squalor and misery in East St. Louis, into the packing house district of Chicago, and nobody looks after them, or cares how they live except the I. W. W. They are wage slaves now. We know it.”

There is no solicitude for workers by employers as such. Haywood cited the Chicago Tribune’s editorial in the early nineties when unemployed by thousands asked for bread. “Give them bread,” said the Tribune, “and put strychnine in it.”

“Do you remember the suffering of that time?” asked Vanderveer.

[Haywood replied:]

Yes, I remember it distinctly; I was out of a job myself.

The working class and the employing class have nothing in common. Look at the sons and daughters of the rich reveling in luxury at Newport, while across the river at Fall River four hundred out of every thousand babies of the textile workers die before they are one year old. At Fall River, misery; over at Newport, monkey dinners for those who are not only unemployed but unemployable.

[Haywood went on:]

I cite an example that I think Mr. Nebeker knows of, as they are friends of his. It was a dog wedding given by the Penrose and McNeil families to a pair of Pekinese pups.

“You are very much mistaken; they are not my friends,” Nebeker protested, turning to the Court to seek vainly for a rebuke to the witness.

[Said Haywood, smiling:]

It may be that I am mistaken, but I supposed that you were friendly with the copper magnates who have employed you.

[He continued:]

We think such people ought to work for what they get. We do not want to take away what they have, but we want to prevent them from taking anything more away from us.

Haywood told of conditions as he found them in the south. In the turpentine camps and in the mill towns among the swamps, the companies furnish negro women with the shacks workers rent, and when a black loses his job, he loses his home and woman together. Also, the companies dispense heroin and other drugs—dope which binds stronger than the chains of chattel slavery.

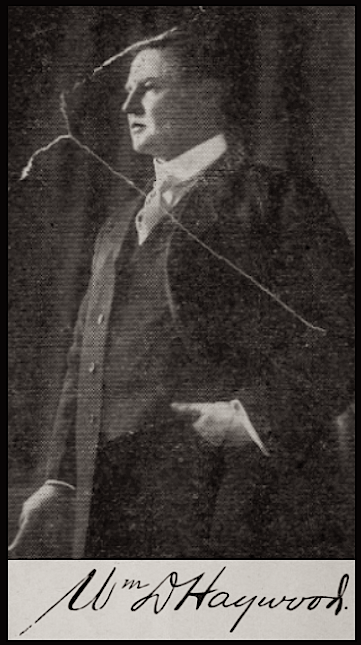

[Photograph, emphasis and paragraph breaks added.]

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

SOURCE

The I.W.W. Trial

Story of the Greatest Trial in Labor’s History

by one of the Defendants

-by Harrison George

—-with introduction by A. S. Embree.

IWW, Chicago, 1919

https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/100663067

Page 181-4: Haywood Takes the Stand, Aug 9, 1918

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=umn.31951d01368761a;view=2up;seq=182

Note: First ad I can find for this book:

Butte Daily Bulletin -page 3

-Mar 5, 1919

https://www.newspapers.com/image/176048912/

IMAGE

BBH ab 1918, fr Haywood at Chg IWW Trial, GEB

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=ucw.ark:/13960/t9q24s822;view=2up;seq=2

See also:

Haywood at Chicago IWW Trial

Evidence and cross examination of William D. Haywood

in the case of the U.S.A. vs. Wm. D. Haywood, et al.

Chicago, General Defense Committee, 1918

https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/003309919

The Cripple Creek Strike:

a History of Industrial Wars in Colorado, 1903-4-5

By Emma Florence Langdon

(this edition, with appendix, would be 1908)

http://www.rebelgraphics.org/wfmhall/langdon00.html

The New York Factory Investigating Commission

https://www.dol.gov/general/aboutdol/history/mono-regsafepart07

The Online Books Page

New York (State). Factory Investigating Commission

http://onlinebooks.library.upenn.edu/webbin/book/lookupname?key=New%20York%20%28State%29%2E%20Factory%20Investigating%20Commission

Remembering 1911 Triangle Factory Fire

Reports

http://trianglefire.ilr.cornell.edu/primary/reports/index.html

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~