Hellraisers Journal, Sunday January 30, 1898

New York City Slum Life – Charity Worker Knows Not Whom to Blame

From the Appeal to Reason of January 29, 1898:

A year ago, I started out to see what the east side of New York was like, and the street which struck me as the most astonishing in its difference from the up-town streets was Goerck Street. It was a warm August afternoon, and the inhabitants of the houses along its street were sitting on the steps and standing about the side walks, to say nothing of those upon the street itself.

I looked eagerly at the faces that should suggest dangerous depravity, and I thought I saw upon almost every countenance expressions of the most satanic cruelty and selfishness. I find that the people who visit me for investigation in this quarter of the city come in the same excited state of alarm at the character of the East Side residents. But after a few month of living among them one entirely abandons any idea of their being so different from other human beings, and there scarcely remains any surprise in one’s mind concerning them, excepting this fact of their living together in crowds, which seems dangerous to moral and physical health. I have found that it is a very common thing for a family of eight to have only one bed; so that possibly an elderly woman afflicted with a disease like rheumatism or cancerous affections in obliged to sleep upon chairs or to lie upon the floor, while the younger members of the family are piled upon the bed, and the poor little children are disposed of anywhere.

One of the most pathetic a cases of sickness that I have attended is that of an elderly women dying of two cancers-a person of lovely disposition, and formerly of the comfortable class of humble citizens-who slept at night upon four chairs with her knees necessarily drawn up somewhat, her impoverished bed near the kitchen stove, while her children slept in one bed. I felt a sharp blow, as it seemed, when I entered her room early one morning and found her still in this condition, and I have known of a number of other instances of the chair-bed. It is the commonest mode of the poor to sleep without additional covering in the coldest weather, and the lack of room is repeated by a lack in every other department of need. The people are thankful if, in the first place, they can pay their rent; next, they desire to keep up their life insurance, which will bury them at death; after that they eagerly seek for shoes; and if any money is left for food (usually beer, coffee and tea, with pork; or, in the case of the Jews, I believe, cakes), the sum of their comfort is as complete as they can make it. The fuel is frequently not paid for, being all sorts of wooden planks, hoops and staves, that are dragged home by the children from places where buildings are being torn down.

Of course the last few years have been disastrous in regard to insufficiency of work for the poor, so that last winter’s experience was no doubt far worse than has been customary. But what I wish to say is, that when we see an overcrowded street, indicating the overcrowded tenements along it, we have a brief statement, so to speak, of the entirely inadequate resources of the poor in every way. Tenement reform has undertaken to bring to the knowledge of the public the horrid condition of the houses hired by the poor, but no descriptions had given me a real knowledge of how dark the passages are in the daytime, how miserably inadequate the water supply, how impossible that the masses of poor in tenements should keep themselves or their quarters clean.

You go into a kitchen which is the principal room of a suite of apartments. The first thing to greet the eye is a huge tub, which to the rest of the room bears the proportion of a large centre-table; the stove is another large feature; the dining-table is still another, covered with a litter of unwashed dishes and crusts of bread. You proceed to enter the room, and the scream of a child calls your attention to a baby on which you have almost stepped as it sprawls upon the floor. You attempt to sit down upon a chair, and find that you run the risk of sitting down on two larger children who are leaning over it. You look around for a place where you may put your cloak or basket, and there does not seem to be a single spot where some unclean article or small human being is not already in the way. If you come in about twelve o’clock, noon, the already crowded apartment is thrown into some consternation by the arrival of the father of the family, who wishes for his dinner-which is never ready for him.

If a baby is sick, it is bolstered up in a rocking-chair on two pillows, or else is brought out of the little bedroom-a dark closet-where it has been buried alive without a breath of air. In this bedroom there is a medley of things-clothing, baby-carriage and boxes. How this mother of a family, who smiles upon you and does her best to be gracious, can possibly keep things clean in so little room, and with so many children, is a question that you cease to ask from that time. You know she cannot possibly do it. It seems strange that so dreadful a place should be of infinite value to a family herding in it, but if the rent money has not been saved or has not been earned, almost the only thought in the mind of each member of the family is that the landlord will turn them out upon the street. This he almost always threatens to do in the most savage manner, though there are some patient landlords who wait a month or two.

I have known a family of father and mother and four children living in one little attic room, with a sort of closet attached, the mother earning all the revenue-because her husband was consumptive-by sewing for the sweat-shop. She finally became ill from overwork, and the severity of the landlord towards her, as she sat in her chair dying, as we supposed, was so terrible that he could not have spoken more harshly. This sort of thing is repeated all the time.

It therefore did not surprise me that one snowy day last winter a man came excitedly into my little room in Schammel street, with a pale, thin man beside him, to whom he pointed, saying this man’s wife was very ill, having a newly bon baby, and being at that moment upon the sidewalk as the snow fell, with her baby in her arms, her other children beside her and no money (because of no work) to find another home. The man who spoke was the foreman of one of the street-cleaning gangs. He said that his own pay would not come in for a few days, or he would give this man ten dollars to settle in other rooms. At the moment I was nearly at the bottom of my purse and had no resources, and was obliged to refuse to aid him. I, the one patient who was living with me then, and my one assistant, passed a very uncomfortable night, and have often wondered since if that mother child survived the severity of their landlord.

I do not blame landlords for insisting upon having their rent; I am not sure even, that I blame them for asking so high a price in the aggregate for houseroom in tumble-down tenements, since they are so often cheated out of their rent, but I CERTAINLY BLAME SOMEBODY OR SOMETHING-I HAVE NOT YET DECIDED TO WHOM THE BLAME BELONGS-for the constant lack of rent money among the poor. I think, however, that the blame attaches to the charitable, who should interest themselves in so vast and primal a need.

Since having a little more money given to me, I have been quite generous about rents, although told by my advisors not touch them. Of course, in caring for a patient, it was out of the question to have her placed upon the sidewalk, and this may give an idea of the way in which I have become involved in paying rents. But if we help the poor at all, we must remember that they claim the necessity of having at least a few inches on a floor under a roof. It is about all they get, at best, in the human hives of which so much is said poetically in fiction and the daily press. If the poor want these hives more than anything else, why should we make our assistance touch everything else first, leaving the question of rents to the last?

I have been told that the rent-money is always found. Of course, after living among the people for a year, I have found that this is not the case. Often the family move without paying back rent, and by making a small deposit for the next month’s housing. One of my patients, suffering from a most terrible cancer and dropsy, which gave her additional agony, was never without perfect terror over her rent money. I could give her fuel, a little clothing (which was generously donated by a city dry goods firm), a bed-she and two daughters slept in one bed, and the son upon a couch in the same room-I could give her food, salves, medicines, doctor’s advice; and after all was done, her face was an expression of misery, always because of the rent which must be paid, and the savage visit which was soon to come from an angry landlord. Now, I think that charity ought to take hold of this matter of rents.

As I go to and fro on my errands, I see the van which is such a familiar sight in front of some door, furniture being hustled into it in great haste, and some tearful woman, with frightened children clinging to her, standing by as the men are bringing out her few chattels, and she looks at me with that fixed expression which implies that the person has come to desperation; and I pass with a guilty feeling that I have no right to escape a responsibility which, somehow, I feel concerning this stranger, whom I might have helped at a moment when she saw no possible help among the hard-hearted companions who refused to respond to her appealing glances.

One disadvantage of crowded tenements is that a family which is very depraved may be placed above a family which is respectable, and hideous noises of drunken people, the screams of women, and violent tossings about of furniture and bodies (which have, to my knowledge, driven sick persons almost insane) bring down large pieces of the ceiling, and render the abode uninhabitable.

These are recent occurrences. Imagine a bent and feeble woman of nearly seventy years of age, racked with rheumatism, feeble from ten years of lonely life in the same tenement, so ill at last with want of food and with pain that she can hardly leave her bed. Imagine her startled at night by an attack upon her door by a strong drunken woman who insists on entering. This drunken woman wishes to enter for the reason that the invalid has made a complaint against her which has caused the landlord to send in a “dispossess.” She explains, outside the door, that she means to kill the old lady inside when she gets in. Upon which the old lady on the inside struggles out of bed, opens her little window, which is barely large enough to allow a person to pass through, and calls in the night for her neighbors on the other side of the backyard to come to her rescue. The drunken woman still threatens and pounds and shakes the door. No one appears to help the poor old woman who is being attacked, and in terror she struggles through her small window and falls some distance into the yard. The consequence is that she has months of illness and semi-aberration.

If these tenements were not often made a place for the indiscriminate herding of anyone who will pay the landlord a few dollars, such contrasts between the inmates would not exist. But the fact is, I could cite many instances truly horrible to show that landlords use very little of their christian light in these dark abodes.

———-

[Photograph and paragraph breaks added.]

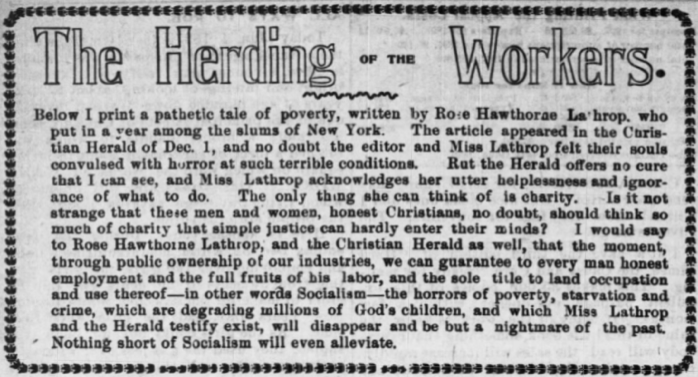

And this further note from the Appeal:

SOURCE

Appeal to Reason

(Girard, Kansas)

-Jan 29, 1898

https://www.newspapers.com/image/66970165

https://www.newspapers.com/image/66970172

IMAGE

Rose Hawthorne Lathrop, 1851-1926

https://www.geni.com/people/Rose-Lathrop/6000000006576336127

See also:

Rose Hawthorne (Mother Mary Alphonsa) 1851-1926

Dominican Sisters of Hawthorne

http://www.hawthorne-dominicans.org/rose-hawthorne.html

http://www.hawthorne-dominicans.org/biography.html

Mother Mary Alphonsa

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mother_Mary_Alphonsa

“I Ain’t Got No Home” – Bruce Springsteen

Lyrics by Woody Guthrie

Photos by Dorothea Lange compiled by Mick Wilbury