———-

———-

Hellraisers Journal – Wednesday March 3, 1909

Mexico City -John Murray Meets with Mexican Revolutionaries

John Murray recently returned from Mexico and has written an article about that experience for this month’s edition of the International Socialist Review. Below we offer the conclusion of that article in which Mr. Murray meets with a group of Mexican Revolutionaries.

Mexico’s Peon-Slaves Preparing for Revolution

BY JOHN MURRAY

[Part IIII]

—–

We turned into the mouth of a narrow street, cobbled from wall to wall. Herbierto knocked at a door. A window swung open above our heads and a voice called out, “Is that the doctor?”

“It is,” answered Senora Moreno. “Is the child still sick?”

“Yes, come in quickly,” replied the watcher, closing the window.

“A sick child?” I questioned, as the door opened and we stumbled through the dark passageway.

“No,” meaningly answered Herbierto. “A sick country, with the revolution as the only medicine.”

And the woman added: “That was the pass word.”

Around an oblong table in the room we entered sat two dozen men, as dissimilar in their appearance as their native land is varied, Mexico is half desert and half tropics and breeds its people small, light-skinned and still-tongued, or swarthy, heavy-boned and voluble, as unlike each other as sand and sage brush are to mountain torrents and black jungle-land.

“A friend from Los Angeles,” explained Herbierto to the group watching me in surprised silence, but as he read my credentials from Magon their faces changed and when the signature was reached, a slim, black-eyed boy warmly grasped my hand, asking the question which seems to echo through Mexico:

“How is Ricardo?”

I gave them greetings from their imprisoned leader. He was their hero, their master-mind, whose years of unflinching struggle against the crushing powers of the Dictator had kept hope in Mexico alive; and in return I heard the news of the revolutionary movement.

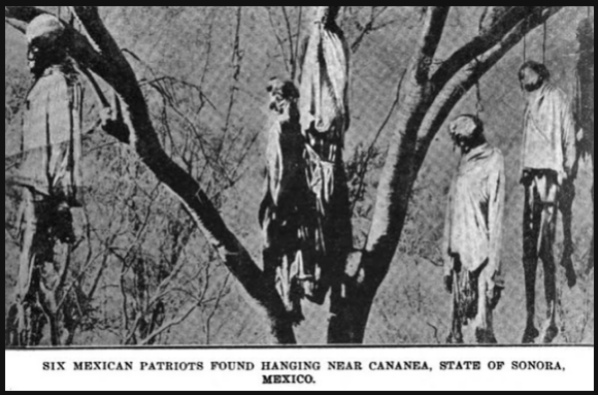

The first to speak was the dark-eyed youth who had just greeted me. “You should have seen what I saw, Herbierto.” (“Listen to him,” whispered my friend, “he’s a cavalry officer stationed with his troop at the Cuartel Nuevo.”) “This morning five hundred Yaquis, chained together were driven through the streets in the northeastern part of the city. To night they are quartered in the Penitenciari and tomorrow they go south to the hot lands of Yucatan. Gaunt skeletons of men and women, covered with a few dirty cotton rags, it was an awful sight. And yet how he feared them—that commanding officer! Would you believe it! though the prisoners were in chains, the inside rank of the regiment surrounding them marched without arms. Four deep on every side, were the guards, but the soldier that walked next to a Yaqui dared not carry a gun for fear that the manacled Indian at his side might suddenly wrest the weapon from him.”

An old man with a massive head and a great shock of hair that fell upon his shoulders like a mane, rose from the shadowed corner of the room. He spoke slowly.

“Yes, I saw them; they are my people, and I ask you members of the Revolutionary Mexicana, when will you rise up as the Yaqui nation has done and fight the Butcher of Mexico?”

Into Herbierto’s eyes there came a look first of amazement and then of sadness. He asked a quick question of the old Yaqui:

“How did you escape?”

I escaped, but not as the Senor supposes, from among the prisoners in the Penitenciari. My escape was made two months ago from the hot lands of Yucatan. A pit of hell is Yucatan, where twenty thousand of my people have been sent to slavery and but five thousand of them remain alive today. Before I die I would again see Sonora, so two of us, feigning sickness, killed a guard with a stone and made our way north, traveling by night. Four days ago the Yaqui with me grew weak with fever and I left him hidden under the bushes while I searched for food. I returned and he was gone. I followed his tracks in the road as soon as it was daylight and came up with him leaning against a tree, dead. It is in all our blood to return back to the mountains and Sonora, and so, the death-chill coming on, my brother rose and walked until he died.

Yesterday I learned that many hundred of my people were to pass through the city; this morning I saw them on their way to the hell from which I escaped, chained together like beasts and driven through the streets by the soldiers of Diaz. Why do these things happen to us? Are we the only Indians in Mexico?

Jumping to his feet, the boyish cavalry officer burst into a fervid reply.

Who is not an Indian in Mexico? The greatest man ever born in the Republic was an Indian. I speak of the noble Juarez, a pure-blooded Zapotec. Diaz himself owes whatever strength he may possess to the strain of Indian blood which flows through his veins. Magon is a Mestizo, and I, thank God! am blessed with an Indian ancestry. Nine-tenths of the life of Mexico is Indian, and this butcher Diaz, is striving to wipe out the best native blood in all Mexico. I mean the Yaquis.

He raised his hand.

Wait, I know what has been said; that the newspapers credit them with murder and devastation. It is not true—not one word in the whole fabric of lies in the subsidized press of the Mexican government. The Yaquis have only defended their lives and the lives of their wives and children against the massacre planned by the agents of Diaz.

Why even the American miners in Sonora are protesting against these butcheries ordered by Diaz.

Listen. Here is a clipping taken from an American mining journal printed in El Paso, “The Southwestern Opportunities”:

“In faithfulness, industry and civilization the Yaqui compares favorably with the Mexicans found in the outlying country. He has few equals in any line of hard manual labor. He is more temperate, more honest and a better citizen than the men of Mexico, who are now taking part in the Yaqui war of extermination. We say this as others might if they had no fear of offending someone higher up.”

But that is not all; this paper tells of a steamship leaving the port of Guaymas, Mazatlan, loaded with Yaqui prisoners, and that while at sea half of the human cargo was forced overboard and drowned. And still more; an English traveler witnessed the imprisonment of many Yaquis; here is what he says:

“They came on foot from the trains, old and young, but with scarce a man or woman of fighting age among them. There were parts of families and remnants of families. One was an old man, a patriarch of the tribe, he tried to walk bravely but his strength was gone. He fell and rose and fell again. When some of the younger ones tried to take him on their arms they were bayoneted back and told to let the old man make the journey alone or die if he could not. Out of the fort at Guaymas the dead were carried daily. Nor was there anyone to tell why they died.”

I added these clippings to my store of evidence against the Mexican Man on Horseback, and the terrible arraignment went on:

But why should any one doubt the bloody-mindedness of the Mexican government in its dealing with the Yaquis when here, in the City of Mexico, it is driving its own people to death by starvation? Are you aware that in no other city in the world is there such a number of dead buried in paupers’ graves as in Mexico? Here is the proof; I will read it to you, and believe me, the paper that prints it would be the last one to overdraw the awful picture, for the Mexican Herald receives a subsidy of $3,000 a month from the hand of Diaz:

“From a total of 408 deaths during the week in the city, in 300 cases the remains were not taken to any private grave, but they were deposited in the sixth-class graves in the Dolores cemetery, where the burial is free. This means that in all these cases the dead persons belong to families absolutely without means, and unable to raise even the small fee for a private grave.

“In eighty-four cases the remains were taken to graves of the third, fourth or fifth class, where the fee is very small, and in twenty-four cases only the remains were taken to graves more or less expensive.

“These statistics are still more significant because it is well known that generally Mexican families are anxious to have their dead taken to private and expensive graves, decorated with monuments, and in many instances they will sell everything in order to have an expensive funeral. The fact that nearly 75 per cent of the dead are taken to the free graves seems to indicate that the families to which they belong have absolutely no means.”

The watching man saw that the piece of irrefutable evidence had made a deep impression upon me, and he followed it up with the fierceness of a hound reaching out after a rabbit:

What now do you think of Porfirio Diaz? Remember, this is the City of Mexico! The show-city of the Republic. A model town where Diaz has laid out great avenues, statuary, fountains, and a three-million-dollar Grand Opera House facing the Alameda. Yet, clinging close to the skirts of all this money-play, is a depth of poverty unknown in any other city in the world.

“Here is more.” He opened a pamphlet and pointed to a tabulation headed, “Nacimientos.”

Follow these figures in the “Boleton Mensual De Estadistica Del Distrito Federal”—they tell a terrible story:

“In the entire Federal District, for the year 1907, there were a total of 21,020 births, while in the city alone there were 20,000 deaths.”

And this proves—think of it, brothers! and may the thoughts sharpen your machetes and load your rifles—that the hand of Diaz is choking the life-blood from dying Mexico.

As the speaker paused, the old Yaqui chief again arose and put the question to the watching group:

Is it not better to die fighting, or even in chains, than to rot in the cities? I ask again, when will the Mexican people rise?

[Herbierto replied, with fierce intensity:]

And I will answer you, for this night, all over Mexico, the chiefs of groups have been given the date. On the 26th of June, one month from today, we will commence our battle for liberty.

The men in the room sprang to their feet, some, in the intensity of the Southern blood, clasping each other in their arms. There seemed to be no question but that Mexico was a seething mass ready to revolt under the very feet of Diaz.

“God ! If we only had the guns!” muttered the young officer at my elbow.

The group began to dissolve, a few leaving at a time and by various exits so as to avoid notice. Escorted by Herbierto, I went into the street.

“Don’t you see that the Diaz house-of-cards is tottering?” His eyes snapped with the eagerness of a successful pursuit as he saw that I was convinced.

“But how was it built in the first place, this one-man government in Mexico?” I put the question, and his answer startled me:

“By the President’s partners.”

At last we had come to the core of the whole matter. If proof of rottenness in the very center of Mexico could be produced, unquestioned evidence that would expose the inner workings of a graft-machine controlled by the President, then the world would be convinced of the revolutionary chasm over which Mexico was tottering.

“The President’s partners,” I repeated slowly; “that story should shake the foundations of Mexico.”

“Yes,” he replied, “but I cannot tell it to you tonight, for in another hour it will be daybreak.”

It was many days before I heard the complete story of the President’s partners. A telegram hurried Magon’s friend northward on revolutionary business to Torreon, while I was guided by the willing hands of the Mexican Liberal Party, southward, through the mills of Orizaba, the political prison of San Juan de Ulua, and the slave-camps of the Valle Nacional. I had no time to lose, for Mexico was planning a revolt in thirty days.

One last picture of the Southern Republic will never leave me—it is typical and happened on the border.

As the train crossed the bridge out of Mexico into Texas, a smooth-faced American engineer in a Panama hat started a cheer. All the Pullman passengers joined in, German, French, English—even the young Mexican who had sat so silently curled up in his corner of the car for the greater part of two days, raised his hat and grinned—for, all questions of patriotism aside, at least as we were out of Mexico. No more gray-hatted rurales, carbine-backed, no more blue-coated gendarmerie, with revolver butt handy on hip, watched our goings and comings.

It is not good to be afraid, and yet in Mexico every one is sooner or later smitten with fear sickness.

To begin with, the Man on Horseback is afraid. And so would you or I be if Mexico were our personal property—as it is that of President Porfirio Diaz—and the Mexican populace eyed us as it eyes Diaz.

I say these things because, today, fear is as much a part of the Mexican atmosphere as its humidity, to be sucked in through the pores, permeating the system. No one can understand life in Mexico without taking into account this universal attribute.

A man in the City of Mexico is crossing the street and his neighbor wishes to call him back. Does he yell out boldly, “Oyes, Martinez!” No, not by any means. “Hist! hist!” is the Mexican’s way of attracting attention. And “hist! hist!” in all ages and in all countries has ever had but one meaning, namely, “Beware! conspiracy!”

Therefore, Diaz, along with all other dwellers of Mexico, is under the spell of “hist! hist!” And he, more than all others, knows why—Mexico is ready for revolt.

Can it be suppressed?

For a time it may—as long as Diaz has the people under cover of his carbines. But it can never be absolutely stamped out.

As Magon, Mexico’s greatest living patriot, has said to me:

IF FOR THREE DAYS THE IRON HEEL OF DIAZ’ REPRESSION COULD BE LIFTED, IN THOSE THREE DAYS WE COULD ORGANIZE SO WELL THAT IN THE NEXT THREE DAYS WE COULD OVERTURN THE DICTATORSHIP.

[Emphasis added.]

[Part III of III.]

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

SOURCES & IMAGES

Quote Freedom Ricardo Flores Magon, Speech re Prisoners of Texas, May 31, 1914

https://isreview.org/issue/101/intervention-and-prisoners-texas

https://books.google.com/books?id=JHOd18yUxrAC

The International Socialist Review, Volume 9

(Chicago, Illinois)

-July 1908 to June 1909

Charles H. Kerr & Company, 1909

https://books.google.com/books?id=Z6o9AAAAYAAJ

ISR Mar 1909

“Mexico’s Peon-Slaves Preparing for Revolution” by John Murray

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=Z6o9AAAAYAAJ&hl=en&pg=GBS.PA641

Meeting with Mexican Revolutionaries

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=Z6o9AAAAYAAJ&hl=en&pg=GBS.PA641&pg=GBS.PA654

See also:

Tag: Mexican Revolutionaries

https://weneverforget.org/tag/mexican-revolutionaries/

Mexican Revolution

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mexican_Revolution

Yaqui People

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Yaqui

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~