C’est la lutte finale

Groupons-nous et demain

L’Internationale

Sera le genre humain.

-Eugène Pottier – Paris, June 1871

Hellraisers Journal: Monday May 2, 1898

From London’s Social Democrat: the Story of an Old Communard, Conclusion

The story of the Old Communard, begun in a French village in the year 1880, ends in that same village in the year 1891, during the month of May:

Father Martin was carried to the cemetery and laid to rest in the little corner of earth reserved for the poor, of whom he had been all his life the valiant defender.

———-

From the Social Democrat of May 1898:

THE OLD COMMUNARD.

(Il en Était)

—–(From the French of J, B. Clément.)

—–

—–

V.

The honest and laborious sallies of the brave William, who was respected largely on account of his herculean strength, at length brought forth fruit.

Father Martin was able from time to time to go and enjoy the shelter of the grand old tree of liberty without being molested. In time, too, the people, who until now had regarded him with an air of contempt, began to acknowledge him at meeting, and sometimes even to salute him with respect.

The old man informed his son of this little alteration of opinion.

“Father,” replied the latter, “I also have observed it; the people who lately shunned me are coming to me again, and are testifying a sympathy which is quite touching. I am happy for your sake, but indifferent as regards myself.”

Father and son were worthy of each other.

* * * * * *

One day William was sent for at the Little Commune to repair some farming instruments. His heart beat fast, as he hastened to the farm, with childish joy.

The work finished, they met in the dining room to settle the business, and at the same time discuss a bottle of wine. They talked over a great number of things, of the Commune, of New Caledonia, and the sufferings endured by the deported. William’s questions were abundant, to all of which Father Martin replied with his great good humour and ardent sincerity.

At each instant the blacksmith took him by the hand and shook it with effusion.

“By my anvil,” cried he at one moment, addressing himself to the sod, “If I had a father such as that I would preserve him in cotton wool.”

“And that is exactly what we are doing, my dear William; but allow me to say that I believe you to be a very excellent man, and, above all, a courageous—–”

“How is that?”

“Our boy Nicholas has several times told us of the scenes you have had respecting me with the country people,” said Father Martin, at the same time holding out his hand.

William, who was quite affected, took the proferred hand, and with tears in his eyes said:

“Ah! many thanks, Monsieur Martin, your kind words are a consolation to me.”

An hour afterwards William and Father Martin walked out arm in arm and sat and chatted beneath the great tree of liberty.

* * * * * *

On this occasion several of the old countrymen came and stood by the two friends, and in time quite a crowd of women and young people collected round the pair.

With touching and persuasive eloquence Father Martin spoke to them of the unmerited miseries endured by the poor, and of their docility and resignation. He dwelt with indignation on the selfishness of the governing classes, and showed them the difference between a bourgeois Republic and a Socialist Republic.

His audience listened with admiration mixed with surprise. Never before had they heard such questions treated in such a manner. The women were moved, the men captivated, and the young people applauded.

As regards William, he viewed Father Martin with admiration, and only interrupted him to repeat:

“Ah! Nom de Dieu, nom de Dieu, that is good! That hits it!”

When it was time to return to the farm, the old man, with the aid of William, rose from his seat and took leave of his auditors, who stood respectfully on one side to allow him to pass.

This open-air gathering was an important event in the village; for days nothing was spoken of but the great capacity of Father Martin, and of his kind sentiments for the poor, for whom he had lived and suffered; the things he had said were recalled and commented upon, and some even went so far as to say that Jesus Christ himself could not have spoken better.

On the evening of this memorable gathering William made a tour of the inns; his face was illumined, and his eyes glistened. He spoke little, however. The triumph of Father Martin sufficed for him; he contented himself by saying to those he met:

“Well, what did you think of it, eh? It was good, wasn’t it?”

To the great surprise of his wife he came home that night singing a couplet of Mother Gregory, and when she inquired the cause of this gaiety he told her what had passed. Then he took her in his arms and embraced her as in their courting days.

“Ah, well, I also love Father Martin,” said the good woman, laughing.

VI.

From this moment there was a complete change in the village. Father Martin was everything and everywhere. If there was any subject to be settled, such as a point of heritage between relations and neighbours, he was elected as arbitrator, and his decision had all the force of law.

“Why should we go and call in men of chicanery and pay them dearly,” said they, “when the old man of the Little Commune knows more than them, and costs nothing?”

Father Martin became also the physician of the place. Armed with his manual of Raspail, he gave consultations and ordered medicines. His patients soon grew better, aided by their faith, and by the fact that the doctor’s visits cost nothing, and that he often helped to pay for the drugs when he did not himself prepare them.

He also became the village scribe; he was the confidant of the young and the counsellor of the old.

In less than a year he had acquired the reputation of a great doctor, a clever business man, a sage and prudent councillor—a fountain of science, and one of the best of men.

* * * * * *

Before the municipal elections took place, the people met and unanimously, with the exception of the mayor, decided to make him a candidate.

“We will make him our mayor,” said some.

“And our deputy,” said others.

And all applauded, and drank to the health of Father Martin, and to the prosperity of the Little Commune.

William, who was also chosen as candidate, was charged with the mission of informing him of the decision of the electors. He acquitted himself with tact, was pressing and suppliant, but could obtain no reply from the old Communard than this:

Give my best thanks to all my friends; tell them that I am deeply touched with this testimony of their confidence and sympathy, but that I desire no position. My only ambition is to remain their friend, and to be as useful to them as I can.”

This decision grieved everybody; and William, having said that he would not revoke it, told them that they should honour him the more for his convictions, and for his disinterestedness. William, who profitted by the popularity and esteem which his old friend enjoyed, was elected the first on the list, and became mayor in place of a noble, a great proprietor of the district, who had shown the greatest hostility to the people at the Little Commune.

William, however, would not accept the position until he had consulted his friend. Father Martin counselled him to accede to the desires of his colleagues, insisting on this ground:

“It is essential on account of your opinions; a Republican mayor can do much good in his commune, and Republican mayors are lacking in France.”

William accepted, promising to do his duty, and added:

“You are right….And then with me there, it is your revenge, my dear Father Martin!”

“No, my friend, it is another, or at least it is the commencement of it.”

“Ah, I understand,” cried William, it is the revenge of the Commune. Vive la Commune!”

And the new mayor and the old Communard, profoundly moved, shook hands heartily.

—–

VII.

Agitated and disturbed as the village of —– had formerly been, in the year 1890 it had become a model commune, the Eden of peasant life, all being relations and friends. The old mayor, unable to bear his defeat, and still less to see himself replaced by a “rustic clown,” as he himself expressed it, in the functions that he had fulfilled for more than thirty years, sold his property, and left that part of the country.

His departure was the occasion of a fête. The people lighted a large fire, and burned the effigy of the nobleman, and the children had quite an extraordinary display of fireworks in memory of the event.

William assisted by his old friend, administered the affairs of the commune to the satisfaction of all. Moreover, he did nothing without first consulting the people, and asking them for their opinion and advice. Undoubtedly he and Father Martin had had the idea of the referendum, and William put it into practice without official sanction. All the projects for local improvements that he had proposed were sanctioned by his council, and he was considered in time, as a man of high ability, and, being more active, more intelligent, and more devoted to his work than the deputy of the constituency, he had obtained from the superior administration and from the State certain advantages which contributed not a little to the transformation and prosperity of the village, so much neglected hitherto.

William no longer was seen in the inns except when he desired to know the opinion of his constituents. The son of Father Martin had put his precious library at his service, and after his day of rude labour, after having forged and welded, done his work of smith, locksmith, engineer, coppersmith, tinsmith, and sometimes even of watchmaker, he would put off his leather apron, wash off the marks of his toil, and go and spend the evening at the Little Commune, reading, studying, taking notes, and educating himself, in company with Father Martin, who in his turn wrote, or read from his old favourite authors: Cabet, Fourier, and Blanqui.

He dreamt of making his little village into a veritable modern Icaria. His brain was simply crammed with good intentions and great projects, and in his moments of fever and expansion he would lean his head on his hand and say to his friend:

“I assure you that something extraordinary has taken place within me! My mind is much greater than before! It boils like a kettle! Oh, how fine it is not to think stupidly, and to see clearly all the good things which you have taught me!”

And Father Martin, proud of his pupil, looked at him with pleasure.

* * * * * *

Towards the end of December, 1890, Father Martin, who was then in his seventieth year, was overcome with a general feebleness. His sight became weak, his eyes affected, his voice hoarse, and his legs scarce able to support his greatly emaciated body.

He lasted thus until the end of April, when, in spite of the lengthening of the sunshine, presaging the advent of the summer, he was compelled to take to his bed.

At the news of his illness all the country people were in consternation, some good wives went secretly and lit the candles in the church, some poured forth prayers to heaven, and others called upon all the saints of paradise to restore the good old man of the Little Commune again to health.

But not the careful nursing with which he was tended, and less still the prayers and candles of the good wives, could abrogate the inexorable law of nature. On the 22nd of May, 1891, at the end of the day, surrounded by his family, and with his cold and frail hand lying in that of his great friend William, who cried like a child, he expired, fully conscious, whispering a last farewell and a last wish for the cause of human emancipation.

The news of the death of the old Communard spread rapidly through the village, but no one would believe it.

“The thing is not possible,” said they.

They had come to think that such a man could not possibly die.

* * * * * *

When doubt was no longer possible, when the day and hour of the interment was known, when it was also known that Father Martin had specified in his testament his desire to be buried without religious ceremony, in the common ground, like the poorest of the poor, a cry of sorrow went up throughout the country.

In a few hours the woods of the environs were despoiled of their young branches, and the gardens and valleys of their flowers, in order to cover the coffin of the good old man with floral crowns and mementoes.

Many were those who offered their shoulders for the honour of carrying his body to its last resting-place. William, who walked with the family at the head of the cortege, arranged all the details of the funeral. And it was in the midst of a sorrowful silence, disturbed only by sobs, followed by all the inhabitants of the country and their children, that Father Martin was carried to the cemetery and laid to rest in the little corner of earth reserved for the poor, of whom he had been all his life the valiant defender.

William had prepared a few words that he had promised to speak on the tomb of his old friend, but, overcome with sorrow, he could only control himself sufficiently to mutter in a sobbing voice, “Good-bye, my dear old friend! Long live the Republic! Long live the Social Revolution!”

And, without comprehending the true meaning of the war-cry they uttered against the established society, men, women, and children cried out repeatedly, “Long live the Social Revolution!”

And the whole assembly passed beside the yet gaping grave, and some dropped on it bunches of flowers, and others let fall their tears.

Although this was Sunday, the greater part of the inns were closed, and at the usual hour could be seen on the door of the ball-room:

“There will be no dancing this evening.”

On the morning of the next day could be seen on the large door of William’s workshop:

“Closed on account of death in the family.”

A. E. L.

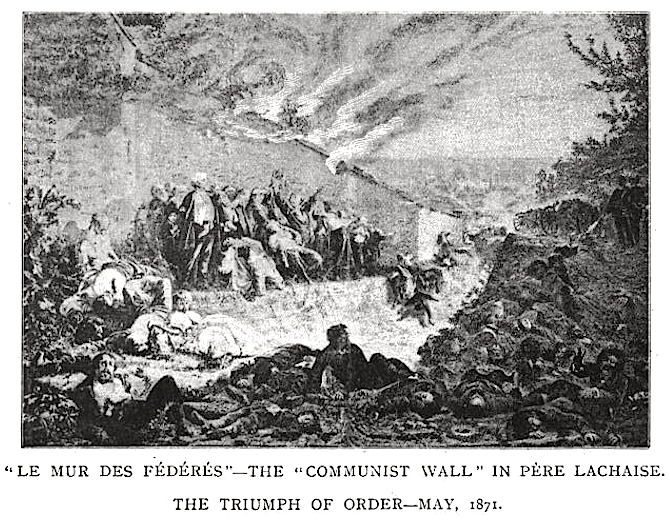

[Photograph added.]

SOURCE

The Social Democrat, Volume 2

A Monthly Socialist Review

-Jan to Dec, 1898

Twentieth Century Press, London, 1898

https://books.google.com/books?id=0isrAAAAYAAJ

SD May 1898

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=0isrAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&pg=GBS.PA131

“The Old Communard” -Conclusion

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=0isrAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&pg=GBS.PA156

IMAGES

Vive La Commune

-Archive of Paris Commune pictures:

http://ciml.250x.com/gallery/paris_pictures.html

Triumph of Order over Paris Commune May 1871, ScDem Mar 1898

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=0isrAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&output=reader&hl=en&pg=GBS.PA66

See also:

Hellraisers Journal: Monday April 18, 1898

From London’s Social Democrat: the Story of an Old Communard

From The Social Democrat: “The Old Communard” a Story Set in a French Village of 1880

Hellraisers Journal, Thursday March 31, 1898

Paris Commune Celebrated Annually by Socialists

From The Social-Democrat: Anniversary of Paris Commune Celebrated by Socialists World-Wide

Tag: Paris Commune

https://weneverforget.org/tag/paris-commune/

Jean Baptiste Clément

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean_Baptiste_Cl%C3%A9ment

The Internationale – Socialist Victory Choir

Lyrics by Eugène Pottier – Paris, June 1871

https://www.marxists.org/history/ussr/sounds/lyrics/international.htm