Up above the strikers stood Annie Clemenc,

girl leader of the miners.

She was not the usual militant Annie Clemenc.

She was saying a prayer for the children.

The Day Book, January 6, 1914

Annie Takes Up Her Flag

On July 23, 1913, 9,000 copper miners of the Keweenaw Peninsula, Upper Michigan, laid down their tools and walked off the job. They were led by the great Western Federation of Miners, and they had voted by a good majority for a strike: 9,000 out of 13,000. The main issues were hours (the miners wanted an eight hour day), wages, and safety. The miners hated the new one-man drill which they called the “widow-maker.” They claimed this drill made an already dangerous job more dangerous.

The mining companies had steadfastly refused to recognize the Western Federation of Miners in any way. They would continue to refuse all efforts at negotiation or arbitration, even those plans for arbitration which did not include the union, and this despite the best efforts of Governor Ferris, and the U. S. Department of Labor. James MacNaughton, general manger of Calumet and Hecla Mining Company, famously stated that grass would grow in the streets and that he would teach the miners to eat potato parings before he would negotiate with the striking miners.

The Keweenaw Peninsula was a cold, windy place, jutting out into Lake Superior from the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. This area was known as the Copper Country of Michigan and included Calumet Township of Houghton County, with the twin towns of Hancock and Houghton ten miles to the south. Calumet Township included the villages of Red Jacket and Laurium.

It was here in Red Jacket, on the third day of the strike that Annie Clemenc, miner’s daughter and miner’s wife took up a massive America flag and led an early morning parade of 400 striking miners and their families. Annie Clemenc was six feet tall, and some claimed she was taller than that by two inches. The flag she carried was so massive that it required a staff two inches thick and ten feet tall. The miners and their supporters marched out of the Italian Hall and through the streets of the Red Jacket to the Blue Jacket and Yellow Jacket mines. They marched silently, without a band, lined up three and four abreast. These early morning marches, with Annie and her flag in the lead, were to become a feature of the strike.

Picket Duty Honored in Spite of Danger

Early on in the strike, MacNaughton put extreme pressure on Sheriff Cruse to request that the Governor send in the National Guard. MacNaughton was a member of the Houghton County Board, a Board dominated by mine operators. Sheriff Cruse owed his job to this board, and Cruse obeyed MacNaughton’s order. The entire Michigan National Guard was sent into the strike zone, over 2,000 men. The County Board also contracted with the Waddell-Mahon strikebreaking agency from New York. Soon private gunthugs began pouring into the Keweenaw. These thugs worked hand-in-hand with Cruse, although, technically he was prevented from deputizing them according to Michigan state law. Scores of mine bosses and scabs were deputized and armed, however, 1700 in all, by some accounts.

The early morning parades, which the strikers and their families regarded as picket duty, became much more dangerous. Nevertheless the parades continued. Every morning at 6 a. m. as the scabs were going to work in the mines, they were forced to face fellow workers whom they were betraying. On Sundays, the parades were held later, after church, with everyone dressed in their Sunday best. Annie came dressed all in white. Streamers flowed down from the mast of her flag on each side and were held by little girls, also dressed in white.

Ana Clemenc, a Young Leader

Annie was born to George and Mary Klobuchar on March 2, 1888 in Red Jacket, the first of five children born to the couple. Her parents were Slovenian immigrants; her father worked in the copper mines. In May of 1906, at the age of 18, she married Joe Clemenc, a copper miner like her father. They made their home in Red Jacket not far from Annie’s parents and the two younger brothers still living at home. The entire extended family was active in St. Joseph’s Catholic Church. In 1910, Annie was elected President of the People’s Slovenian Women’s Lodge #128 of the SNJP (Slovenska Narodna Podporna Jednota-Slovene National Benefit Society.) She was only 22 years old at the time. She would continue as President of Lodge #128 until 1914, listed in the records as Ana Clemenc, President. Annie was also a member of the JSZ, Jugoslojvanska Socialisticna Zveza (Yugoslav Socialist Federation) which was affiliated with the Socialist Party of America. There are photos of Annie during the strike, wearing her Socialist Party pin.

From Proletarec

The editor of Proletarec (Proletarian), Frank Savs, came from Chicago to the strike zone to cover the strike. Proletarec was the official voice of the JSZ. This story, by “Striker (translated),” was published September 2nd:

The women who carried flags in front of us, they laughed out loud every time the soldiers got mixed up; their screams and claps echoed throughout the city.We noticed one morning, when we were going to march, the Waddell bastards driving around fast in cars-the deputy superintendent riding with them-going from mine to mine and gathering together scabs, who were dressed in overalls and carrying their lamps. They collected around 40 scabs and showed them to us by the road, thinking it would take away our courage. But they got it badly wrong. When we marched past them and their bosses, we began to laugh heartily and make fun of them. We asked one another, so that the bosses could hear: “Where’s the one thousand and two thousand scabs, the mine owners always talk about? Are these all you can show?”

After completing the march we went to the Italian Hall. Organizer Strizic suggested that women now speak in various languages, which we approved with applause. Ana Klemenc and Katarina Junko spoke in Slovenian.

Mrs. Klemenc recommended that the women should make the effort with all our strength to help our husbands in the battle to victory, because victory will also benefit women and children. Degenerate men, scabs, will fail the women and children…

ARRESTED AND RELEASED TO CHEERING

Annie was arrested Wednesday, September 10th, in Calumet along with five other women. As they attempted to convince a miner not to go back to work, the women were accosted by Cruse’s deputies. The women fought back against the deputies but were, eventually, arrested. Three hundred supporters followed behind the women as they were taken to the Calumet jail. The crowd remained outside the jail for two hours, cheering loudly for their release. The crowd followed the six women as they were taken to the court of Judge William Fisher, and the cheering began again as Annie, Maggie Aggarto, and the four other women were released on their own recognizance. The women came out of the court undaunted, shouting and clapping their hands. They marched down the street with their supporters following behind cheering and shouting.

The six women were ordered to appear again in court the next week.

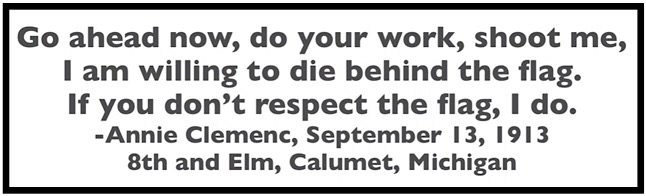

“If this flag will not protect me, then I will die with it.”

Just days a few days later, Annie was found, back in the thick of the fight. On the following Monday morning, September 13th, she led a march of 1,000 strikers and many women supporters through the streets of Calumet as was her usual routine. At the corner of Eighth and Elm, they were confronted by the militia and armed deputies. A soldier on horseback used his saber to knock her flag from her grasp. A striker came to her aid and was pushed to the ground by another soldier who ripped the silk fabric of the flag as he slashed about with his sword. Annie was also knocked to the ground. The flag was stomped into the mud by the horses of the guardsmen. Big Annie hung on to the flag as soldiers tried to take it from her, shouting:

Annie was rescued by other marchers and escaped with only a bayonet blow to the right wrist. The strikers’ march was driven back by soldiers on horseback and by the rifle butts of infantrymen. Deputies joined in on the attack swinging their clubs. The strikers and their supporters retreated to the Italian Hall with Big Annie and her flag, now muddied and slashed.

THE BEST WEAPONS

On Wednesday October 1st, Annie was arrested yet again, this time by a Major Harry Britton. Annie was marching at the head of 400 strikers, carrying her huge American flag as usual. They were on their way to perform picket duty at the mines when they were stopped by deputies and cavalrymen with Major Britton in command. Major Britton attempted to arrest Annie, claiming she spit at a scab. When the Major used his sword to beat back a striker who came to Annie’s aid, other strikers joined in the fray. Cavalrymen then charged into the midst of the strikers. Major Britton bragged:

Excited horses prancing about are the best weapons.

He describe the results with satisfaction:

..a striker with his head bleeding, blood flowing down over his shirt, [was] half-staggering along the road.

Annie was arrested along with nine others. Annie was released the next day, and went immediately to union headquarters to lead another strikers’ march with her immense American flag.

“Woman’s Story”

This account of picked duty was written by Annie Clemenc and published October 2nd on the front pate of the Miners’ Bulletin, the official voice of the Western Federation of Miners within the strike zone:

At Seventh Street Tuesday morning a party of strikers met a man with a dinner bucket. I asked him: “Where are you going, partner?” He replied: “To work.” “Not in the mine are you?” “You bet I am.” after talking with him a while his wife came and took him down the street. She seemed very much afraid.He had just gone when a couple of Austrians came along with their buckets. I stepped up to one I knew: “O! George, you are not going to work, are You? Come, stay with us. Don’t allow that bad woman to drive you to work. Stick to us and we will stick to you.” He stepped back, willing to comply with my request.

Then the deputies came, caught him by the shoulder and pushed him along, saying: “You coward, are you going back because a woman told you not to go to work?” The deputies, some eight or ten of them, pulled him along with them.

A militia officer, I think it was General Abbey, said: “Annie, you have to get away from here.” “No, I am not going. I have a right to stand here and quietly ask the scabs not to go to work.”

I was standing to one side of the crowd and he said: “You will have to get in the auto.” “I won’t go until you tell me the reason.” Then he made me get in the auto. I kept pounding the automobile with my feet and asking what I was being taken to jail for. The officer said: “Why don’t you stay at home?” “I won’t stay at home, my work is here, nobody can stop me. I am going to keep at it until this strike is won.” I was kept in jail from six-thirty until twelve, then released under bond.

THE CHILDREN’S MARCH

On October 6th, Annie led a parade of 500 children through the streets of Calumet. These were the the children of copper miners who had been on strike for eleven long weeks. One little fellow carried a sign which sums up the entire struggle:

PAPA IS STRIKING FOR US

Many of the children were willing to face truancy charges in order to make this show of support for their fathers. The kept press was quick to seize on the story, declaring in lurid headlines:

YOUNG SYMPATHIZERS WITH STRIKING MINERS REFUSE TO STUDY

The fact that these young children were suffering hunger and deprivation had not bothered these same newspapers. Neither had they bothered themselves with worry over the fact that these same children often lost their fathers in mining accidents which were, tragically, all too frequent in Michigan’s Copper Country.

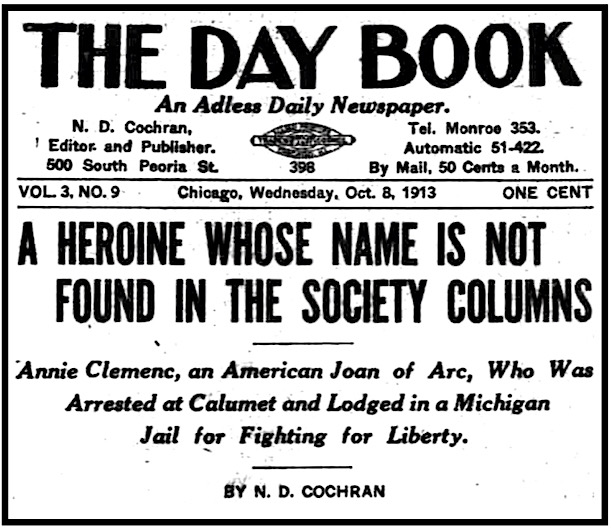

“Annie Clemenc, an American Joan of Arc”

In the October 8th edition of Day Book, N. D. Cochran profiled Annie. The article was written at the time that Annie was in jail:

I have met Annie Clemenc. I have talked with her. I have seen her marching along the middle of the street, carrying that great American flag. She is a striking figure, strong, with firm but supple muscles, fearless, ready to die for a cause. A militia officer said to me, “If McNaughton could only buy Big Annie, he could break the strike.” I don’t believe all the millions of dividends taken out of the Calumet and Hecla mine could buy her.

I walked fully two miles with her…and I thought what glorious men and women America would produce if there were millions of mothers like Annie Clemenc. I thought that one Annie Clemenc, miner’s wife, was worth thousands of James McNaughtons.

Annie Clemenc is more of an American in my esteem than the spineless but well-meaning governor of Michigan. And as manhood goes, she’s more of a man in fighting quality, in sand, in courage, in heroism than Governor Ferris.

If Annie Clemenc is in that dirty little jail now, the American flag would be better off on top of that jail than over some courthouse. Where she is there is love of liberty and courage to fight for it. Annie Clemenc isn’t afraid to die.

This article was later reprinted in the Miners’ Bulletin, and in labor newspapers across the country. Big Annie Clemenc of Calumet was becoming a heroine to workers across the nation.

From the El Paso Herald:

STRIKERS PARADE IN FIERCE BLIZZARD

Calumet, Mich., Nov. 8.-During a fierce blizzard which brought between eight and ten inches of snow in the Calumet copper mining region today, the striking miners and their wives and daughters paraded in half a dozen towns. A party of 100 strikers, led by Mrs. Annie Clemenc, established pickets around mining properties here. Eighty were arrested on a charge of violating the federal court’s injunction against picketing. They were released on their own recognizance to appear in court next week.

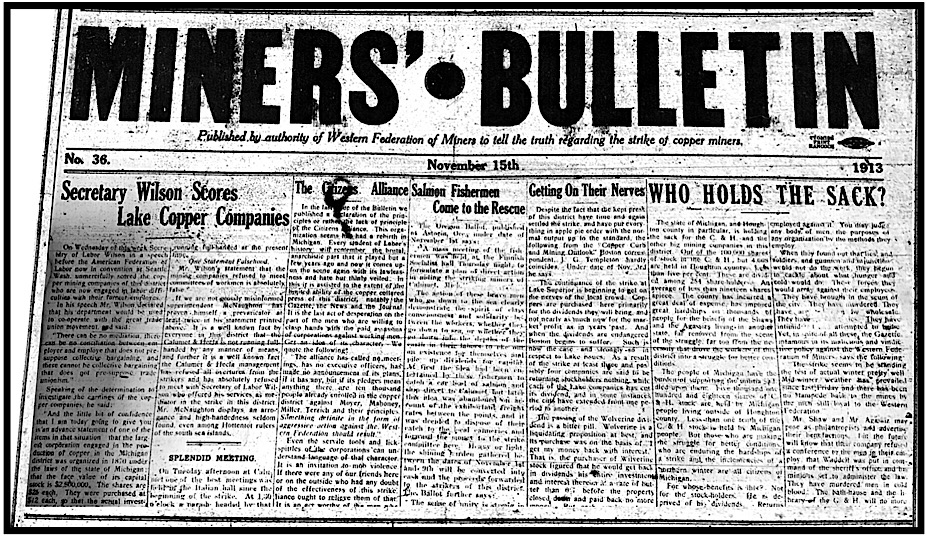

From the Miners’ Bulletin

The story of Annie’s conviction was printed in the November 15th edition:

The case of Mrs. Annie Clemenc of Calumet charged with assault and battery (pushing an insulting scab off the sidewalk), tried in the circuit court at Houghton last week, resulted in her being found guilty as charged. The incident occurred at Calumet during the early days of the strike, and had it occurred at any other time would not have received passing notice, but during these turbulent times, a scab, being a very precious article must not be disturbed. Mrs. Clemenc has been under bonds since her preliminary hearing which will be maintained until she receives her sentence in January.

The names and addresses of the twelve men finding her guilty were also published.

Planning a Christmas Party for the Children

The Calumet Women’s Auxiliary had been organized in September. It was granted a charter as #15, and each woman who joined, became a card-carrying member of the Western Federation of Miners.The women soon began planning a Christmas party for the children of the strikers to be held on Christmas Eve at the Italian Hall in Red Jacket. The afternoon party for the children was to be followed by a party for the adults in the evening. As president of #15, Annie, took the lead in planning for the event, and she raised donations to buy gifts for the children. Candy, hats, mittens, and toys were purchased. For many of the striker’s children, these would be their only Christmas presents.

The Man Who Cried Fire

The party began at 2 p. m. as planned. Elin Lesh was at the front door checking for union cards. At 3 p. m. went inside the hall to assist Annie at the stage. There was a Christmas program and, after that, the children where able to come onto the stage to get their presents. Annie and her helpers had some difficulty in getting the children to come onto the stage in an orderly way, and Annie warned the children to wait their turn. There was a lot of noise and confusion in the hall which was crowed with about 700 people, perhaps 500 of them children.

At about 4:40 pm, a man came up the stairs. On his left, at the top of stairs, were double doors leading into the main hall. He went through those doors, and just inside the main hall, he cried, “Fire, Fire.” The man then ran down the stairs, out of the building, and disappeared down the street. The man was wearing a hat pulled down low with the brim over his eyes; he had on a long coat with the collar pulled up, and on his coat was pinned a Citizens Alliance button. The Citizens Alliance was anti-union vigilante organization sponsored by the mine operators.

The cry of fire was picked up, and a panic started with a rush for the stairs which lead to the exit at the front of the building. Within just a few minutes that stairway was packed with party goers, many of them suffocating in the crush. The stairway was packed 6 feet deep at the bottom of the stairs, and for the entire length of the stairs-30 feet. The stairway was 5 feet 9 inches wide.

Silent Night

Charles Meyers, who ran a shop downstairs was the first to arrive. He came through the front doors to the second doors at the bottom of the stairs. These doors were open and did not open inward, as so many now believe. Meyers could clearly see that people were trapped and suffocating. He attempted to pull some children free but that proved impossible. He made his way upstairs through a window and continued to assist with the rescue. Dominic Vairo came from his saloon downstairs and had very much the same experience.

The Red Jacket fire station received the first alarm at 4:45 pm, and the fire fighters were on the scene within a few minutes. The fire whistle was also used to call forth the mobs of the Citizens Alliance, the Waddell men, and the deputies. And soon the street outside of the Italian Hall was filled with gunthugs. Frantic relatives and friends of those inside also began to gather. There is no evidence that any of the gunthugs held the doors shut, but the deputies and Waddell men were none to gentle in the way in which they pushed back on the crowd. A Finnish man was severely beaten. Some inside the hall later stated that they thought the deputies had come to kill them all.

As Annie and the women at the stage realized the calamity that was upon them, they first attempted to quiet the panic, and then began to help with the rescue effort. The untangling of the bodies could only be done from the top of the stairs. It was long slow work, lasting for more than an hour. And when it was finished, the bodies of 62 children and 11 adults were laid out on the floor of the hall with some outside in the snow. Annie later remembered:

…a deputy gave me a child. I poured some water on it, but it was dead already.

Out on the street was big Joe Mihelchich kneeling in the snow and sobbing before the bodies of his three children, Paul-5, Agnes-7, and Elizabeth-9. Joe was well remembered as the giant who had tossed deputies around like toys as they tried to arrest him, threatening them and everyone in the vicinity with two lighted sticks of dynamite. He now shook with sobs as he stroked the faces of his dead children, a broken man.The bodies were taken to the Red Jacket Village Hall, used as a temporary morgue, for identification. There were losses from the SNJP woman’s lodge, all friends of Annie: Mary Smuk lost her 5-year-old daughter, Mary Stauduhar lost her 7-year-old daughter, and Mary Cvetkovich lost her husband. Also, many of dead were members, or related to members, of Annie’s own local of the Women’s Auxiliary.

Dust to Dust, Ashes to Ashes

The mass funeral was held on December 28th. There was a shortage of coffins, especially for the children, and neighboring communities were contacted. Funerals were held at three Finnish churches, as well as an Italian church, a Croatian church, and a Slovenian church, most likely Annie’s. And then began the march to Lakeview Cemetery.

Estimates are that 50,000 took part in the march to the cemetery. Annie led the way carrying her flag, now draped with black crepe. Snow began to fall as they marched. Church bells could be heard from near and far, tolling for the dead. The little white caskets were covered in flowers. It is said that the weeping from the cemetery could be heard in the town, two miles away.

Fifty men came marching behind the caskets, chanting “Nearer My God to Thee” in the old style of the Cornwall mining districts. There was a band at end of the march. The entire length of the road to the cemetery was lined with mourners, many brought from other towns by special coach.

The dead were laid to rest with eulogies in Finnish, Austrian, English, and Croatian. E. A. McNally, attorney for the strikers, gave a long address. He spoke for all, the living and the dead, when he said:

It is not charity we want; it is justice.

A newspaper later describe Annie at the graveside:

Up above the strikers stood Annie Clemenc, girl leader of the miners. She was not the usual militant Annie Clemenc. She was saying a prayer for the children.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

SOURCES

Quote re Annie Clemenc at Mass Funeral, Day Book p4, Jan 6, 1914

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045487/1914-01-06/ed-1/seq-4/

Tall Annie

-by Virginia Law Burns

MI, 1987

Big Annie of Calumet

-by Jerry Stanley

NY, 1996

Death’s Door

The Truth Behind Michigan’s Larges Mass Murder

-by Steve Lehto

MI, 2006

Annie Clemenc

& the Great Keweenaw Copper Strike

-by Lyndon Comstock

SC, 2013

Miners’ Bulletin

“Published by authority of

Western Federation of Miners

to tell the truth regarding

the strike of the copper miners.”

-of Oct 2, 1913

-of Nov 15, 1913

Copies in possession of Janet Raye.

El Paso Herald

(El Paso, TX)

-of Nov 9, 1913

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn88084272/1913-11-09/ed-1/seq-1/

IMAGES

Annie Clemenc w Flag, ISR p342, Dec 1913

https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v14n06-dec-1913-ISR-riaz-ocr.pdf

MI Strikers Parade, Annie w Flag, Survey p127, Nov 1, 1913

https://archive.org/details/thesurvey31survuoft/page/127/mode/1up?view=theater

Quote Annie Clemenc, Die Behind Flag, Mnrs Bltn, Sept 16, 1913

-per Comstock p42

https://books.google.com/books?id=0-FGAgAAQBAJ

Heroine Annie Clemenc, Day Book p1, Oct 8, 1913

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045487/1913-10-08/ed-1/seq-1/

HdLn Annie Clemenc Guilty, Miners Bulletin p1, Nov 15, 1913

“Harvest of Death”-Italian Hall Massacre, Miners Bulletin p1, Dec 28, 1913

Copies in possession of Janet Raye

See also:

Tag: Annie Clemenc

https://weneverforget.org/tag/annie-clemenc/

Tag: Michigan Copper Country Strike of 1913-1914

https://weneverforget.org/tag/michigan-copper-country-strike-of-1913-1914/

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~