—————

—————

Hellraisers Journal – Tuesday November 1, 1921

Winthrop D. Lane on West Virginia’s Coal Field War, Part III

From The Survey of October 1921:

[Part III of III.]

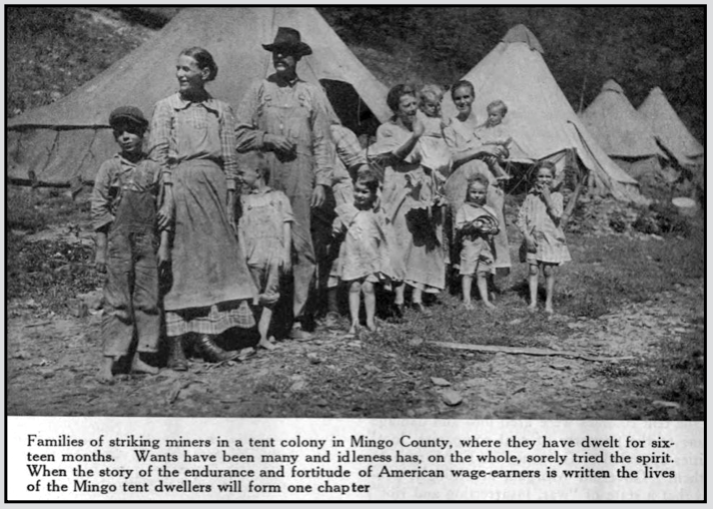

What, meanwhile, has the state government been doing to bring peace and order to a situation so intense as this? For four months it has been maintaining martial law in Mingo County, for one thing. This is the third time within a year that some form of military control has been proclaimed in that strike-swept area; on the other two occasions federal troops were called in. Today the state is using its own forces, a rifle company of the national guard, which is now being reorganized. When a “three-days battle” occurred along a ten-mile front in Mingo County on May 12, 13 and 14, during which shots were exchanged by union and non-union elements, the tent colonies were fired into and damage was done to the property of coal companies, local authorities appealed to Governor E. F. Morgan to assist them. Governor Morgan, accordingly, proclaimed that a state of “war, insurrection and riot” existed in Mingo County, and directed Major Thomas B. Davis, acting adjutant-general, to proceed there and with the aid of the state constabulary and deputy sheriffs to place the region under martial law.

The legality of this procedure was assailed by the United Mine Workers of America when its members were arrested under the martial law proclamation. The state Supreme Court of Appeals held the edict invalid. The reason given by the court was that the proclamation could only be enforced by the occupancy of the zone covered by a military force, and that the state constabulary and deputy sheriffs were not a military force.

Thereupon Governor Morgan, to provide such a force, issued a new proclamation ordering the enrollment of the “unorganized militia” of the county. This, it is said, was done under an old statute. Every person liable to military duty in the county became subject to draft in this new militia. Two companies of sixty-five men each were formed and these citizens and residents of the county shouldered guns and proceeded to give effectiveness to the governor’s proclamation of martial law. Two months later the first company of the reorganized national guard took their place.

Both military and civil authorities are clothed with the power to make arrests in Mingo County, but only the civil courts are trying persons for offenses. For some time the jail has had over one hundred men, some of whom, according to the jailer, have no charges against them of which he is aware. C. F. Keeney, president of District 17 of the United Mine Workers of America, and Fred Mooney, secretary, are in the Mingo jail, charged with complicity in the murder, several months ago, of two men. Both officials say that they were attending a convention of the State Federation of Labor in Huntington at the time and know nothing of the killing. Mr. Keeney and Mr. Mooney are also under indictment in Logan County for having taken part in the recent “armed march,” and Mr. Keeney is under a third indictment in Boone County, charged with carrying a pistol. Neither is anxious to secure bail, the reason being that when released they would be liable to further arrest and incarceration in Logan County, where their lives might not be safe.

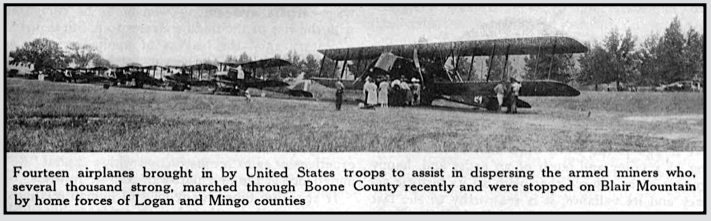

The state has also called in a thousand United States troops to suppress disorder in connection with the “armed march” in late August of union miners through Boone County toward Logan. These troops were still there October 14. Without doubt this march was a formidable affair. There is reason to believe, however, that it would have ended more quietly than it did and that the five thousand or so miners in it would have disbanded without serious rupture of the peace, if a group of state constabulary who were opposing their advance had not made an apparently uncalled-for attack upon a little town named Sharples near the place where the miners were assembled. This fanned their expiring purpose to new energy.

The object of the demonstration seems to be shrouded in uncertainty. One account has it that the miners intended to march to Mingo County, crossing Logan County in their path, and protest against the enforcement of martial law there and the abuses that they understood were being committed against their fellows. According to this version, what they really hoped for was to get federal troops called into Mingo County as a better alternative than the régime then in force. Another story, credited to the operators and some residents of Logan County, is that they intended to seize the mines in Logan and compel the employers to recognize the union. A third is that theirs was a vague, leaderless uprising without deliberate purpose or objective. Whatever its motive, there is no doubt that it spread considerable terror among the inhabitants in its path, especially those in Logan County who were fearful of a real attack.

The miners succeeded in advancing to a point part way up the slope of Blair Mountain, the high ridge that separates Boone and Logan counties. Here they formed a line some fifteen miles in length, with the crest of the ridge before them. One end of the line was at Madison, in Boone County, and the other at Blair, in Logan. Meanwhile, a large force of hastily recruited citizens, deputy sheriffs, non-union miners and others from Logan and Mingo counties were waiting on the other side of the ridge under the leadership of Don Chafin, Logan County sheriff. A small number of state constabulary as well, held part of the defending line. Shots were exchanged in large numbers and several union miners, the exact number unknown, were killed. Three persons in the Logan County forces were killed. A small airplane was used by the Logan defenders and a number of bombs were dropped on territory held by the invading miners. No damage was done in this way.

The federal troops came upon the scene by two routes. One command entered behind the Logan, or defending, forces, and the other slipped in between the opposing lines themselves. The Logan forces were thus sandwiched between two lines of United States soldiers, and the miners, on the other hand, were effectually barred from further advance. No fighting took place after the arrival of Uncle Sam’s men. The miners disbanded and went home, many of them being disarmed by the soldiers on their way. The extent of depredations seems to have been small, and in several instances members or officials of the union reimbursed storekeepers whose goods had been taken. The “army” of marchers seems to have imitated military tactics sufficiently to commandeer railroad stock and some automobiles.

The aftermath of this march has been a crop of indictments. A special Boone County grand jury has indicted 302 persons, 189 of these being charged with “insurrection” and most of the others with carrying pistols. Everyone arrested, according to the prosecuting attorney, will be held under heavy bond or in jail to await the November term of the circuit court. But Boone County has been restrained in comparison with Logan, where nine hundred people are wanted in connection with the demonstration. The miners, however, who took part in or witnessed the march are taking this matter into their own hands. Over a thousand of them, according to Colonel C. S. Martin, who is in charge of the federal troops there, have already left the scene of the disturbance. Many of them are taking their families with them and leaving no addresses behind.

The reorganization of the state’s national guard is proceeding under authority granted by the legislature last spring. This is another public measure directed at the conflict over unionism. West Virginia’s former national guard had ceased to exist when its members were mustered out of the United States army at the end of the war. Today the reorganization is being speeded up. One company is already in active service and is giving effect to the proclamation of martial law in Mingo County.

Fifteen companies will be formed this year, although the ultimate strength of the guard will be much larger. The distribution of these companies is significant. Fourteen of the whole number are being concentrated in or near the non-union coal fields. One more will be recruited in Mingo County; one in Logan County; two at Welch, county seat of McDowell County; two at Bluefield in Mercer County; three at Huntington, which commands quick and easy entrance to the non-union fields; three at Charleston, only thirty miles from Logan County; one at St. Albans, near Charleston, and one at Weston. Only the last is not in position to be of immediate service in protecting the non-union territory. Meanwhile, three-fourths of the state, the eastern and northern sections, are in spite of applications for them going without any companies of the national guard.

A disagreement evidently exists in regard to the admission of members of labor unions. Major T. C. Davis, of the adjutant-general’s staff (not the Major Davis who is in charge of martial law in Mingo County), said that no member of a union would be admitted. “It is a rule of the national guard,” he said, “not to take in union men. They don’t make good members. At any rate, that is the policy we are adopting here.” This was later denied by Adjutant-General J. H. Charnock, in charge of the reorganization. “We want the best men we can get,” said the adjutant-general. “If a member of a union is a good citizen we have no objection to him. We do aim to exclude radicals and undesirables. Our support is coming from business and professional classes for the most part.” The two officers agreed that the guard was to act as “a strictly neutral organization.”

We have now seen the elements that compose West Virginia’s industrial struggle. What is to be the outcome? Two groups, each with roots reaching outside the state, are engaged in what is little different from civil war. From time to time the strong arms of the state and federal governments are interposed to separate the combatants. Many of the instruments of modern warfare have been used; airplanes have hovered over the state, bombs have been dropped, machine-guns have rattled; tear gas and Big Berthas remain to be used. But does public reliance solely on such methods of suppression get anywhere in the long run? Colonel Martin, in command of the United States soldiers who came to check the recent march, sees the situation clearly. “We have quieted the disorder for the moment,” he said. “The fundamental causes remain. Whatever produced this disturbance may give rise to another.”

[Emphasis added.]

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

SOURCES & IMAGES

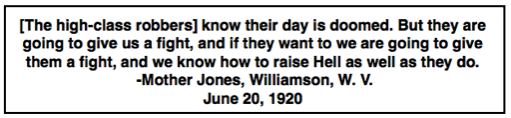

Quote Mother Jones, June 20, 1920, Speeches Steel p213

https://books.google.com/books?id=vI-xAAAAIAAJ

https://digital.library.pitt.edu/islandora/object/pitt%3A31735035254105/viewer#page/1/mode/2up

The Survey, Volume 47

(New York, New York)

-Oct 1921 to Mar 1922

Survey Associates, 1922

https://archive.org/details/surveycharityorg47survrich/page/2/mode/2up

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.31210013389174&view=2up&seq=7&skin=2021

-Oct 29, 1921-page 181:

“West Virginia, Civil War in Its Coal Fields”

by WD Lane, Part III

https://archive.org/details/surveycharityorg47survrich/page/180/mode/2up

See also:

Hellraisers Journal: From The Survey of Oct 29, 1921:

“West Virginia, The Civil War in Its Coal Fields” by Winthrop D. Lane,

Part I Part II

Tag: Winthrop Lane

https://weneverforget.org/tag/winthrop-lane/

Civil War in West Virginia

-by Winthrop David Lane

B. W. Huebsch, Incorporated, 1921

https://books.google.com/books?id=3hYtAQAAIAAJ

https://archive.org/details/civilwarinwestvi00lanerich/page/n7/mode/2up

https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/001432266

Tag: Mingo County Coal Miners Strike of 1920-1922

https://weneverforget.org/tag/mingo-county-coal-miners-strike-of-1920-1922/

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

They’ll Never Keep Us Down – Hazel Dickens